Winsor McCay (1867? ~ 1934) is known as the Father Of Animation. He did not actually invent animation, experiments in bringing drawings to life had been done since the days of magic lanterns in the 17th century and wasted little time once the film era began. By 1906 the British film-maker and illustrator J. Stuart Blackburn, the Frenchman Emile Cohl and the Spaniard (working in France) Segundo de Chomon had made some rudimentary animated shorts. They were very crude with halting and jerky movements that would barely qualify as animation at all by later standards and it would take a serious cartoonist to bring the new art form to life.

Winsor McCay's background was a mystery even to himself; he gave various different dates and locations for his birth. His background is clear enough however. His family were of Scottish background and lived in Woodstock, Ontario, Canada and they immigrated to America around 1868. American census reports from 1870 and 1880 show a Zenas Winsor McCay (his full name) born in Canada in 1867, living in Spring Lake, Michigan. However no birth or baptism record has ever been found on either side of the border. He would later claim to have been born in 1871 in America, but that date (if not the location) is impossible according to the 1870 census report, and Winsor himself would admit that he didn't really know the truth.

FROM ILLUSTRATOR TO CARTOONIST;

At any rate the young Winsor (not surprisingly he quickly dropped the "Zenus") was drawn to art as a child and was encouraged by his parents to take art lessons which included illustration, etching and stained glass, all useful skills for a future animator. By 1889 he had moved to Chicago to further his art studies and become a commercial illustrator. He would then get a steady gig as cartoonist for Cincinnati newspapers while working a side gig as an entertainer drawing caricatures in rapid time in front of audiences. He would develop a distinct stamp moving past the dense Victorian look of Thomas Nast and Richard Outcault to a more open and flowing style more influenced by the newer Art Nouveau school out of Europe. By 1903 he had made enough of a name for himself that he got a high profile job with the "New York Herald" as an editorial cartoonist. Richard Outcault, who was the most succesful cartoonist in America also worked at the Herald. Outcault is considered the first modern cartoonist having developed the idea of using panels to tell a story instead if using a single stand-alone drawing as Thomas Nast had done. He also made use of dialog bubbles to better show which character was speaking. This enabled Outcault to have serial stories and introduce the first regular characters starting with the hugely popular "Yellow Kid" and later "Buster Brown" strips. Outcault and the younger McCay did not get along however and would become rivals as the younger artist became more popular. McCay would later move to William Randolph Hearst's "New York Journal" and "Evening Telegram". McCay would later have a contentious relationship with Hearst over the rest of his life.

Working for Hearst McCay started out as an editorial cartoonist but he also tried to develop a strip of his own. After several abortive experiments with names like "Sister Little's Sister's Beau" and "Phoolish Phunny Phrolics", McCay got a gig as illustrator for a comedic series called "Percival Slathers" about a meek, elderly gent and his hopeless attempts to make his way in high society. This was not an actual comic strip but a series of illustrated short stories. Little is known about this series including the identity of the writer but it is probably not McCay given that it's writing style is unlike anything McCay ever did. Nor did he ever mention it in later years and in fact copies were only recently discovered. The artwork for "Percival Slathers" is competent but not particularly noteworthy although it may have helped him finally get a strip of his own with "Mr. Goodenough" in 1904. "Mr. Goodenough" was variation on "Percival Slathers" with another upper-class twit, in this case an indolent millionaire, and his lackluster attempts to become sociable. The short run strip is largely forgettable although it does show flashes of a more individual visual style.

After these abortive attempts McCay developed a popular character strip called "Little Sammy Sneeze" in 1904. As a character "Sammy Sneeze" was simple in the extreme. Sammy was a small boy who in every strip would try to stifle a sneeze which would in the final frame explode with catastrophic results; bricks would fall from buildings, animals would stampede, crowds would flee in panic. And that was it, Sammy had no dialog or even a real personality, he was just a force of nature. But if the strip had little of substance it had a striking visual sense that surpassed Outcault's. McCay was an superior draftsman combining a very realistic view of human figures and the way they moved along with clean and uncluttered backgrounds. At a time when Victorian illustrators were fond of excessive detail McCay experimented with minimal backgrounds, including some that used only stark black or white, he also "broke the fourth wall" by having characters at times bust out of their panel. Even today some his "Sammy Sneeze" strips look much like the comics of the 1960's while Outcault's clearly belong to the Edwardian Era and Nast's to the Victorian.

"LITTLE SAMMY SNEEZE";

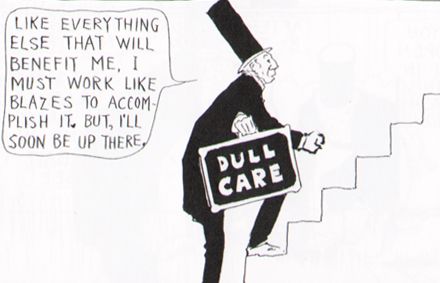

"Sammy Sneeze" was popular but it was aimed at kids and it's lack of a real story must have been somewhat limiting since McCay also developed another strip (under the pen name of Silas) called "A Pilgrim's Progress" which had a continuing story about a middle-class man forever trying to free himself of a briefcase embossed with the words "Dull Care" and live a carefree life on "Easy Street" only to have the case return in the last panel. The strip was an odd allegory named after John Bunyan's Puritan religious novel (the character was named Mister Bunion) that seems quite clunky to modern audiences but once again the artwork is excellent if less elaborate than "Sammy Sneeze". Around the same time McCay had developed another even more important strip called "The Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend". This strip was truly ground breaking both for it's subject matter and it's amazing visuals.

"PILGRIM'S PROGRESS";

"Rarebit Fiend" did not have a regular character and it's plot, such as it was, never changed. In every strip a character, after eating a "Welsh Rarebit" (a bun covered with melted fermented cheese) has a dream with bizarre and often terrifying hallucinations. These dreams could be incredibly complex, characters could find themselves shrinking to the size of ants or growing to such massive size that they strode through the city like King Kong, or caught in traffic which slices off various limbs, trapped in a museum chased by dinosaur bones come to life, chased by an army of their own doppelgangers, floating in space, climbing an endless staircase surrounded by inky blackness, or eaten by a giant snake while other jungle animals stroll the city streets wearing business suits. While some strips were bizarre slapsticks other were quite dark as one which showed the dreamer being buried alive in the best Edgar Allen Poe tradition while his widow flirted with his best friend. There had simply never been anything remotely like it and the strip was a sensation leading McCay to develop the idea more fully into his best known strip "Little Nemo In Slumberland".

"DREAM OF A RAREBIT FIEND";

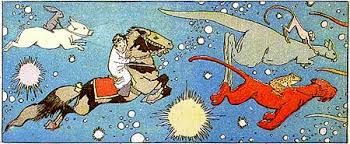

"Little Nemo" was another small boy, who while he sleeps enters into a rich dream world through which he travels. "Slumberland" is a lush fantasy land with floating castles made of mirrors, mountains made of cake and ice-cream, armies of snowmen who come to life, flying cars and pirate ships, beds that sprout legs and run away and other dream sequences we have since seen repeated in more modern cartoons from Disney's "Fantasia" to Betty Boop and Bugs Bunny toons to the Simpsons.

"LITTLE NEMO IN SLUMBERLAND";

Besides Nemo the strip had other regular characters such as a Little Princes, an escaped African savage boy called "Imp" and a troublesome cigar chomping clown with a five-o'clock shadow called "Flip". The "Little Nemo" strips were the most elaborate ones yet done by McCay or anyone else. Eventually taking up an entire page in full colour, each panel was incredibly detailed and crammed with Art-Nouveau architecture and costumes. As always the characters looked realistic and showed a close attention to the human form and movement.

LITTLE NEMO"

In 1909 McCay would try one more straight forward strip aimed at adults called "Poor Jake" about a hapless (and once again speechless) working class jack-of-all-trades who is constantly over worked by his lazy millionaire boss who in turn takes all the credit. This was an obvious political allegory and shows how McCay's focus had changed from his earlier "Mr. Goodenough", in fact Poor Jake's boss looks like Mr. Goodenough which may not be a coincidence. Other than this point the strip was decidedly minor and lacked the imagination or visual flair of his other strips and it was short lived.

McCay's strips displayed a mastery of visuals as well as a vivid imagination but they also showed his one weakness; he had some wildly creative ideas but he was a poor writer. His dialog was full of long rambling run-on sentences that seemed to be crammed into the character's word bubbles as an after thought. Sometimes they were cut off in mid-sentence as if McCay tossed off the dialog after the artwork including word bubbles were already done, which was probably the case. While McCay could come up with a visual gag he simply could not write a punchline. McCay did in fact come up with some creative and quite advanced story ideas or at least concepts but he was only interested in exploring them visually. "Sammy Sneeze" and "Rarebit Fiend" did not have proper plots or stories at all and while "Pilgrims Progress" actually did have a fairly complex idea as it's basis, the stories were episodic and again basically identical. That left "Little Nemo" as the only major McCay strip which had proper stories although again McCay's dialog is still somewhat clunky.

This brings us to McCays second weakness; character development. Almost all of McCay's characters, from Sammy Sneeze to the various Rarebit Dreamers to Poor Jake were completely passive. They took no initiative nor did they even give much reaction to any of the plights they found themselves in. The Dreamers were subjects of their hallucinations following which they then made a bemused comment while Sammy Sneeze and Poor Jake were speechless. Mr Bunion and Mr Goodenough would make occasional and fitful attempts to take some sort of action only to fail leaving them to merely shrug and comment wryly. Even Little Nemo who seems at first glance to be an explorer in a fantastical world is mostly an observer rather than taking any initiative and he has no real personality, he is not mischievous or even really curious, he never displays any particular emotion. The same is largely true of his friend the Little Princess leaving only the irascible character of Flip The Clown, and to a lessor extent the playful African Imp (who is also speechless) as the only McCay characters to have a real personality.

CARTOONIST TO ANIMATOR;

Early on in his career Winsor McCay had performed in public by doing quick caricatures while narrating his work to an audience. By 1906 as his work became famous he was lured back to vaudeville to perform in an act in which he would do quick drawings and appear to make them move and age while an orchestra played. Sometimes he shared bills with acts like jugglers, dog acts, knife throwers, accordion players, yodelers and comics like W.C.Fields, Will Rogers, Charley Case, John Bunny and the Keaton Family (featuring a young Buster). This success led to attempts to turn "Little Nemo" into a stage show with a live cast as had been done earlier by his rival Richard Outcault with his "Buster Brown" strip. McCay's backers gave him a huge budget of $100,000 to play with which allowed for an elaborate set and a score by composer Victor Herbert. The play ran for two years as a touring show to sell-out shows while McCay continued to tour with his own vaudeville act. He also continued to somehow find time to do his regular newspaper strips. In 1906 director Edwin S. Porter did a short version of "Rarebit Fiend" which included some groundbreaking double exposure special effects.

"DREAM OF A RAREBIT FIEND"

In 1911 McCay started to experiment with film. There had been some earlier attempts with animation without much success, but McCay's unique skillset of exceptional draft work, attention to detail and rapid fire drawing ability along with a vivid imagination made him the perfect pioneer to make animation truely come alive. He chose as his subjects the characters from "Little Nemo". McCays first strips were really just experiments in trying to make the sort of flipbooks used by children come alive. McCay developed the method of using thousands of painstakingly drawn pictures drawn in sequence on rice paper to show incremental movement. This early strip doesn't have a story but it must be remembered that this cartoon was not intended to be shown in theatres but was instead part of McCay's vaudeville act. McCay would stand to the side of the stage and pretend to interact with the characters getting them to jump, dance and throw objects. As such it was still groundbreaking and contemporary audiences were spellbound by the new medium. Literally every animator since has used the same methods and the strip still looks modern. In fact in it's fluidity of movement McCay's strips are easily superior to those of Hanna-Barbara, Rankin-Bass, Krantz Studios or Cambria Studios fifty years later.

"LITTLE NEMO & FRIENDS" (1920's theatrical reissue with intro);

The next year McCay left the "Herald" in a dispute over money and was hired by William Randolph Hearst for his empire. The "Herald" tried to claim copyright over McCay's characters but McCay eventually sued successfully to keep them. Still in that year he made a more elaborate strip with it's own storyline but without Nemo called "How A Mosquito Operates" which had an amazingly lifelike sequence of a giant mosquito attacking a sleeping man until it gets so full it explodes. The film was based on one of McCay's "Rarebit Fiend" strips and shows an accuracy of movement and anatomy that is still stunning, and a little creepy. This toon was also added to McCay's vaudeville act, although unlike the previous film this one had enough of a story that it could stand alone.

"HOW A MOSQUITO OPERATES";

Following this artistic triumph McCay would develop his most famous animated character; "Gertie The Dinosaur" in 1914. McCay had drawn dinosaurs in earlier newspaper strips but by adding movement and facial expressions he was able to give Gertie a real personality, rather like a hugely overgrown but playful puppy. Once again this toon was designed to be part of McCay's vaudeville act wherein McCay would introduce the shy Gertie who would be coaxed into doing tricks, dancing and playing catch. At the end McCay would appear to walk into the screen and ride off on Gertie's back. Besides Gertie the toon is notable for having full backgrounds and depth perception unlike the earlier toons. The importance of Gertie to future animators can not be overstated. McCay had created a lovable and believable animal character which could move and even show emotion. Later animators like Nat Fleischer and Walt Disney would list Gertie as one of their greatest influences. Virtually all subsequent toons for the next half century would look and move essentially like Gertie.

"GERTIE THE DINOSAUR" (EXCERPTS);

Unfortunately McCay's days a vaudeville performer would suddenly come to an end when his employer William Randolph Hearst decided that McCay was spending too much time on his animation and his live show and not enough working on the newspaper and would ban McCay from vaudeville. Hearst did however give McCay a substantial raise to cover the loss of his performing revenue and McCay was allowed to do outside work illustrating advertisements and sheet music books. "Gertie" was later re-shot for the movie theatres with a lengthy prologue added to explain the process and take the place of McCay's in person interaction with Gertie. This filmed intro (which takes up almost half of the short) starred Winsor McCay as himself and included a cameo from vaudeville comedian John Bunny. Although largely forgotten today John Bunny was the first film comedy star and was internationally famous and a large influence on WC Fields, although he isn't given much to do here. Still this is one of the few chances to see Bunny since few of his films survive. It's also the only chance to see Winsor McCay, by this time in late middle age and balding. He bills himself as "The Inventor Of Animation" which is close enough to the truth to be excusable.

"GERTIE THE DINOSAUR" (full film short);

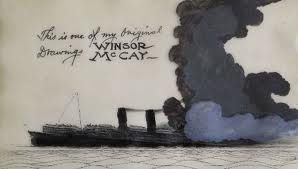

America's entrance into World War One in 1917 gave McCay a chance to make what would become his cartoon masterpiece; "The Sinking Of The Lusitania". This toon was a piece of anti-German war propaganda which Hearst could not object to. The Lusitania was a British passenger liner (and a rival to the Titanic) which was sunk by a German U-Boat in 1915 with a heavy loss of life including many Americans and which became a cause-celeb in the run up to America's declaring war. The cartoon shows the ship leaving New York then intercepted by a U-Boat which fires a torpedo causing a vivid explosion. The rest of the strip shows the ship's sinking, a side bar naming a few celebrities who died on board, the survivors splashing in the water, and it ends with a shot of a mother holding an infant sinking beneath the waves.

Starting in 1917 and finished in 1918 the entire strip took 25,000 individual drawings each done by hand by McCay himself with a couple of assistants using a new technique he developed, drawing on clear cellophane cells instead of rice paper as before. The strip shows McCay's usual attention to detail and careful observation of form and movement. Notice the undulating waves, each done individually. Then the billowing curtains as the ship passes the Statue Of Liberty. Next the strip gains menace with the arrival of the surface running across the surface with it's crew running to battle stations, a scene that looks so real it almost looks like an actual film. Then comes the spectacular explosion scene which again looks stunningly real rather than a cartoon explosion. The ship's slow motion sinking with it's smokestacks billowing out a thick oily cloud while the passengers and crew scramble down ropes or jump overboard has a brutal beauty that belies the term "cartoon". So to the final shot of the drowning mother and child, a scene actually taken from a well-known recruiting poster by American artist Fred Spear. The only discordant note (aside from the jingoist narration at the end) is the shot of a couple of cartoonish fish speeding out of the way of the speeding torpedo, not that the shot is badly done of course but it's cutesy look doesn't really fit with the serious nature of the rest of the strip. Even taking into account that this strip is in black and white the lush detail and realism of the strip would not be equaled until the full colour features done by Walt Disney and the Superman cartoons done by the Fleischer Brothers of the late 1930's

"THE SINKING OF THE LUSITANIA" ~ 1918;

With Mcay's reputation as "The Inventor Of Animation" secure he resumed making cartoons building on the new animation cell technique which allowed him to make more detailed strips based on his fantasy comic strips "Little Nemo" and "Rarebit Fiend". By 1921 he had released three complete strips; "Bug Vaudeville" which builds on the research done for "Mosquito" to create a fantasy vaudeville act made up of giant dancing bugs. There is also an intro featuring Flip The Clown from Little Nemo strip.

"BUG VAUDEVILLE" ~ 1921

"The Pet" featured an animal that eats so much that it grows to massive size and proceeds to stomp through a terrified city like King Kong until it is killed by the air-force. The unidentified pet in question looks like a cross between a puppy and a teddy bear but for some reason it meows like a cat.

"DREAM OF A RAREBIT FIEND; THE PET" ~ 1921;

"The Flying House" was the most psychedelic toon yet in which a man attaches wings to his house and flies away to escape from creditors.

"THE FLYING HOUSE" ~ 1921;

After his animation career was abruptly stopped there were a few unfinshed projects such as this lush fragment of some centaurs in a Art Nouveau forest.

"THE CENTAURS";

LATER CAREER:

In 1921 Hearst once again invoked his exclusive contract to ban McCay from further animation work. Since 1918 Hearst had allowed McCay to do animation presumably because of the increased publicity and prestige and on the assumption that since these cartoons were done to be shown in movie theatres rather than on the vaudeville stage they would still leave McCay to continue to do his work for Hearst's papers. However hand drawn animation is extremely time consuming, especially if it's done with McCay's painstaking attention to detail and so Hearst once again ordered McCay to drop his animation work and concentrate solely on his newspaper work which included his weekly strips as well as editorial cartoons. As before Hearst promised McCay a bonus which he apparently did not pay however and when McCay's contract ended in 1924 McCay quit and moved to a rival paper, taking Nemo with him. Hearst tried to continue the Nemo strip under a different name with artist Mel Cummin but was not successful and McCay was lured back in 1927. Besides his usual strip work on of the noteworty jobs done for Hearst in later years was sketching the scenes from the Lindburgh kidnapping in 1932. Winsor McCay suffered a massive stroke and died in 1934 aged about 55. After his death Hearst once again tried briefly to keep "Little Nemo" alive with the hapless Mel Cummin, with the same lack of result.

INFLUENCES AND LEGACY:

Besides being massively influential for their artwork, strips like "Little Nemo" and "Rarebit Fiend" are fascinating for their subject matter. In his exploration of dreams McCay seems to be channeling the theories of his contemporary Sigmund Freud although there is no evidence they were even aware of each other. McCay's fantasies also anticipate the French Symbolists and the later Surrealists and Beats although again there is no evidence they knew of his work. McCay seems to occupy his own unique space, reaching similar conclusions to the avant-garde without being in anyway a part of it. In this he resembles another American contemporary, the composer Charles Ives, who was experimenting with musical rule breaking at the same time Arnold Schoenberg was shocking Europe in spite of the two men being quite unaware of each other's work. When Schoenberg was much later exposed to Ives's work he was shocked to find there had been a like-thinking contemporary in conservative middle America. One wonders what Salvador Dali, Marcell Duchamp, Andre Breton or Man Ray would have made of this American newspaper cartoonist's work.

McCay himself never listed any influences leaving to much speculation as to where he took his ideas. Possible artistic influences include earlier newspaper cartoonists Thomas Nast, Joseph Keppler, and especially Fredrick Burr Opper, Gustave Verbeek, Ralph Barton, James Mongomery Flag, Charles Dana Gibson and Richard Outcault. Impressionists Alfonse Mucha and Toulouse-Lautrec, Art Nouveau illustrators Aubrey Beardsley and especially Arthur Rackham. French Symbolist painter Gusatve Moreau, European artists Gustave Dore and eccentric French fanatsy illustrators Isadore Grandville and Albert Robida. A later influence may have been the dream-like films of George Melies.

As for the thematic ideas behind McCay's fantasy strips like "Rarebit Fiend" and "Little Nemo" with their explorations of dreams and the subconscious influences aside from Freud (who McCay never mentioned as having read) included Lewis Carroll ("Alice In Wonderland"), J.M. Barrie ("Peter Pan"), Washington Irving ("Rip Van Winkle"), Oscar Wilde, Edward Lear, Charles Baudelaire, Robert Louis Stevenson ("Dr.Jekyll & Mr Hyde"), Arthur Conan Doyle ("The Devil's Paw"), H.G.Wells, Jules Verne, Bram Stoker, William Blake, Mark Twain ("A Connecticut Yankee In King Arthur's Court"), Ambrose Bierce, O.Henry and of course Edgar Allen Poe. Another obvious but lesser known writer was Harle Oren Cummins who wrote a series of short stories called "Welsh Rarebit Tales" in 1902 which involved characters having hallucinations after eating Welsh Rarebit. An even more obscure known writer was Edward S. Ellis a popular author of dime novels who wrote "The Steam Man Of The Prairies" about a giant robot (with appropriately striking cover art by an unknown illustrator) in 1865. Although not especially well educated formally McCay was quite well read and known to be a fan of Shakespeare, Yeats and the Romantic Poets Shelly, Keats and Byron who he could quote from memory, along with the Bible.

As an animator McCay's importance simply can not be overestimated. McCay did not actually "invent animation" but he developed, or at least perfected the basic technique of drawing on layers of clear cellophane cells which gave him the ability to make his cartoons far more elaborate, multi-layered and lifelike as well as longer than was possible using the older rice paper flipbook method. It is no exaggeration to say that all subsequent animation used the cell method until computer animation was invented. Unfortunately it turned out that while McCay himself did get the credit he deserved he not get the money he should have from his invention of cell animation. McCay had a lackadaisical attitude towards money and business and did not bother to patent his invention even when urged to do so. He was at first happy to let other share his invention for free until a rival cartoonist named John Randolph Bray went behind McCay's back and filed patents himself on McCay's various animation and camera inventions and then had the colossal gall to turn around and sue McCay for copyright infringement! The no doubt outraged McCay counter-sued and eventually won a settlement which forced Bray to pay royalties to McCay.

Artists and animators who have paid tribute to McCay's influence have included Walt Disney, Nat and Dave Fleischer ("Betty Boop" & "Popeye"), Tex Avery ("Droopy"), Chuck Jones & Friz Freling (Warner Brothers cartoons including Bugs Bunny & Daffy Duck), Ub Iwerks ("Flip The Frog"), Walter Lantz ("Woody Woodpecker"), Ralph Bakshi ("Fritz The Cat", "Spiderman" & "Rocket Robin Hood"), Peter Max ("Sgt.Pepper") and Matt Groening ("The Simpsons").

Cartoonists and Comic Artists include George Harriman ("Krazy Kat"), Al Capp ("Lil Abner"), Nick Cardy ("Tarzan"), Hal Foster ("Prince Valiant"), Chester Gould ("Dick Tracy"), Bud Fishe ("Mutt & Jeff"), George McManus ("Bringing Up Father" & "Rosie's Beau"), Joe Shuster ("Superman"), Bob Kane & Jerry Robinson ("Batman") and of course Dr. Seuss. Modern comic artists include Art Spiegelman and R.Crumb. Non comic artists include Muarice Sendak ("Where The Wild Things Are") and Scf-Fi illustrator Frank Paul. Film makers include Fredrico Fellini, Terry Gilliam and Tim Burton.

Perhaps the greatest tribute came from Walt Disney who in 1955 did a TV special on the history of animation which included a section on Winsor McCay. Disney invited McCay's son Bob (also an artist) down to Disney Studios and told him "Bob; All this should have been your dad's".