George Harriman (1880 - 1944) is, along with Winsor McKay and Richard Outcault, one of the founding figures in cartooning and animation in the twentieth century. It was they who established the look and approach of all modern cartoons in the Edwardian Era. Previously the archetypal cartoonist was Thomas Nast with his carefully detailed drawings, densely packed with details, he was the apex of Victorian cartoonists. Starting in the 1890's a new style emerged, more open and flowing and less literal minded, led first by Richard Outcault whose newspaper strips "Gasoline Alley" (with it's "Yellow Kid" character) and "Buster Brown" established many of the conventions followed by most cartoon strips to this day; recurring characters, dialogue bubbles and muti-pannelled strips that told a story. He favoured simpler backgrounds and a cleaner, less detailed look. Outcault's wildly popular strips were followed by Winsor McCay's refinements in such classic strips as "Litle Nemo", "Dream Of A Rarebit Fiend", "Little Sammy Sneeze" and "A Pilgrim's Progress". McCay, a better and more imaginative illustrator than Outcault, introduced a cleaner, more flowing style that looks strikingly modern and more in tune with contemporary art movements such as Art Nouveau, Futurism, Expressionism and Cubism. George Harriman would complete the evolution of the modern comic strip. (note; I've already written extensively about Winsor McCay here).

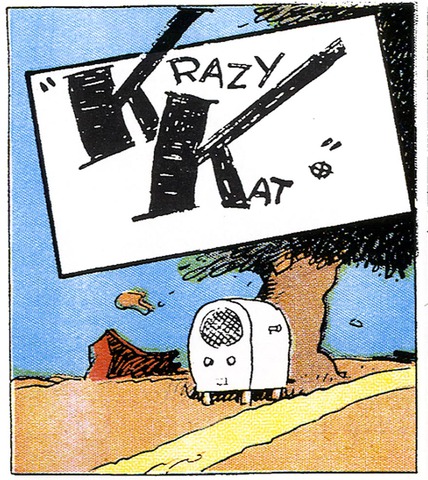

Winsor McCay, for all his brilliance and imagination, was still literal in his visual style, although not in his themes. His human characters still look exactly like human characters, only slightly exaggerated. His animal characters look and act like animals, they do not (usually) talk or wear clothes like people. By contrast in "Krazy Kat" George Harriman's characters were animals who walked upright, talked, wore clothes and acted like humans. They also did not look like literal illustrations of animals, as McCay would have done, but rather as crudely stylized versions. They were symbols of human characters rather than literal representations. In fact there were no humans at all in "Krazy Kat". The background scenery in "Krazy Kat" was equally stylized, usually made up of flat featureless plains with an occasional oddly shaped tree, cactus or mesa in the distance and angular clouds in a starless night sky. Nast's backgrounds were full of meticulous and literal detail. Outcault's were less densely packed but still literal minded portrayal of contemporary scenes. McCay experimented with fantastical and bizarre backgrounds but they were always presented as the character's visiting a fantasy or dream world and readers would accept them as such. McCay's strips always started and ended with the characters in the "real world" before sending them to the fantasy world. Harriman's "Karzy Kat" however was a self contained world were everything was strange and talking animals ran free, there was no "normal world" with regular humans to return to.

Since the heyday of McCay and Harriman in the 1900's all cartoons and animation fall into one of two schools; either McCay or Harriman. McCay's influence is shown in all the superhero, horror and western comics from the 1930's to today, strips like "Doonesbury", "Bloom County", "Blondie", "Denis The Menace", "Henry", "Andy Capp", "Scooby Doo", "Dick Tracy", the epic animated features from Walt Disney, the Fleischer Brothers classic "Superman" toons and the (much) lower budget toons of the 1960's television such as "Spider Man", "Rocket Robin Hood", "Captain America", "Thor" (all from the same Krantz Studios) and "Space Angel", "Captain Fathom", "Clutch Cargo" (all from Cambria Studios) and modern toons like "Beetlejuice", "Inspector Gadget" (both from Nelvana) and parodies like "Space Angel" ending ultimately with Anime. The Harriman influence is shown in the early Disney Mickey Mouse toons, the Warner Bros toons of Chuck Jones, Friz Freling and Tex Avery (especially "The Roadrunner" and "The Pink Panther"), Ub Iwerks "Flip The Frog", the Fleischer Bros "Betty Boop" and "Popeye" toons, "Peanuts", "Broom Hilda", "B.C.", "The Wizard Of Id", "Felix The Cat", "Fritz The Cat" and modern abstract and absurdest toons such as "South Park", "Ren & Stimpy" and "Sponge Bob Square Pants". "The Simpsons" and "Family Guy" manage to combine both schools.

Unlike Winsor McCay, whose early work already showed an individual style, George Harriman did not start out as an especially noteworthy artist, let alone a groundbreaker. Born in 1880 in New Orleans, Harriman's background has always been something of a mystery. Possibly even to him. It is believed that he was of Creole background. Creoles had a different tradition from Southern blacks; they had never been slaves, they were educated, middle class bilingual and Catholic. However in the Jim Crow south Creoles were officially considered black and as such there was little opportunity for them to advance. Accordingly his parents immigrated to Los Angeles when he was about ten years old. In later years Harriman (who had a dark complexion and dark curly hair) would tell people his background was a mixture of Spanish, Cuban, Greek and Turkish although it's firmly established his family had been in New Orleans for many years. He did not have any particular art training but was talented enough to land a job at seventeen at the Los Angeles Herald where he did occasional advertising and political and sports cartoons. At this point his style was quite conservative in the style of established Victorian cartoonists such as Thomas Nast, Joseph Keppler and Fredrick Burr Opper. In 1900 he hopped a freight train to New York where he eventually landed a job with humour magazine "Judge" before being picked up by the Pulitzer chain. Harriman had a regular job as a sports cartoonist (in the days before photographs could be easily reproduced sports sections relied on cartoonists) as well as doing a series of comic strips.

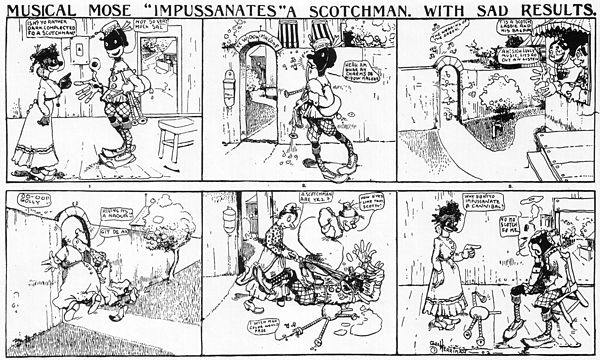

These strips started with "Musical Mose" in 1902. Mose was a character from blackface minstrel shows, a comic hustler who spoke in an exaggerated dialect. By any modern standard these strips are blatantly racist even taking in to consideration Harriman's own mixed race background, although this type of humour was quite common at the time. He also did a number of one-off strips on various subjects. By this time his style had advanced to the more free flowing and less cluttered style of Richard Outcault, then the most popular cartoonist of the day.

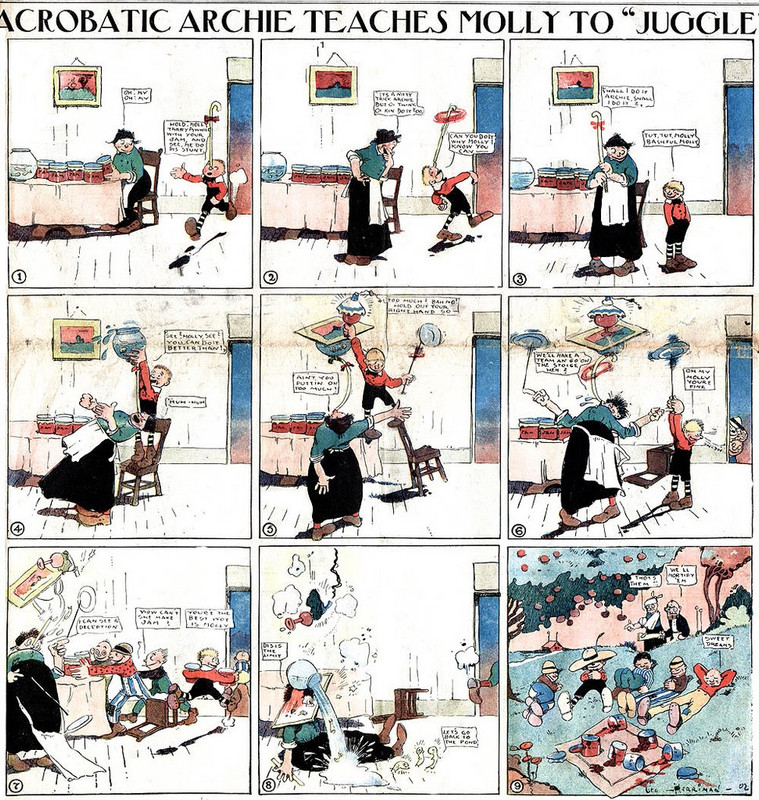

Between 1903 and 1910 Harriman developed a series of often short lived strips with titles like "Professor Otto & His Auto", "Acrobatic Archie" (about a mischievous child), "Two Jolly Jackies" (about two sailors), "Lariat Pete" (a cowboy), "Major Ozone", "Home Sweet Home", "Baron Mooch", "Mr Proones The Plumber" and a number of others. Some of these strips were popular enough and at this point his style had again evolved to resemble contemporaries strips like Bud Fisher's "Mutt & Jeff", "Bringing Up Father", and "The Katzenjammer Kids". By this time Harriman had shown himself skilled in working within the established styles of his contemporaries but he had yet to develop a style of his own.

"Acrobatic Archie"

In 1909 Harriman developed his first all-animal strips with "Alexander The Cat", "Daniel & Patsy", "Polly & Her Pals" and "Gooseberry Sprig". In 1910 Harriman (who had moved back to Los Angeles in 1906) returned to New York and started another strip,"The Dingbats", about a wacky family. This was not a particularly noteworthy strip and would have no doubt been a short lived as the rest but that year Harriman stumbled on to his iconic characters. In one "Dingbats" strip he found some empty space at the bottom of the panels so he added in a separate strip about a cat and a mouse. The strip reversed the dynamic between cat and mouse where instead of having the cat chase the mouse, the cat was instead shown as a lazy innocent tormented by a bullying mouse. Soon the cat and mouse became popular enough to merit their own strip and by 1912 they had they had a stand-alone strip called "Krazy Kat".

The story-lines of "Krazy Kat" were simple; Krazy was a sweet, innocent Kat who was blindly in love with Ignatz, a bad tempered mouse. Ignatz however despised Krazy and responded to Krazy's flirtations by tossing bricks at Krazy's head. This provoked another character (brought in from the earlier "Gooseberry Sprig" strip) called Offisa Pup, a squat bulldogish type wearing a policeman's uniform to intervene. Offisa Pup had a crush on Krazy (which the rather clueless Krazy never seemed to notice) and would try to protect Krazy by throwing Ignatz in jail, only to have Krazy rescue him. There were also a number of secondary characters who dropped in from time to time to cause trouble or comment on the bizarre love triangle. The sexuality of Krazy caused much debate with Harriman himself at first unsure, referring to the character as both he or she at various times. Krazy is wearing a ribbon with a bow around his/her neck but at other times the bow appears to be a men's wing collar instead. Eventually Harriman decided that Krazy was an "asexual sprite". The characters all spoke in a difficult lingo that combined street slang, black dialect from minstrel shows, Yiddish and other puns and deliberate misspellings from vaudeville "ethnic" routines that were not always easy to dis-cipher but which fascinated many poets, writers and musicians. This may have reflected Harriman's New Orleans origins and a knowledge of minstrelsy and ragtime slang. These prose flights alone might have been enough to earn Harriman a footnote as an influence with later Beatnick figures like Slim Gaillard and Lord Buckley, with Jack Keruac himself citing Krazy Kat as a favorite.

One major difference between McCay and Harriman is that while McCay was clearly a brilliant and imaginative illustrator he was no writer. His dialogue was clunky, wordy and lacking in meter. Consisting of many repetitive run-on sentences, his dialogue often had to be crammed into the word bubbles, sometimes even running out of room. This suggested that McCay worked out dialogue only after the artwork, as an afterthought. Similarly McCay's characters, however well drawn, were two dimensional, lacking any real personality and never taking any initiative in their stories. They were always mere observers; McCay would send them into some bizarre fantasy or dream world, lovingly created, which they would observe and comment on until he brought them back. End of story. The only exception to this rule was the character of Flip, an unshaven, cigar chomping, misanthropic clown from Little Nemo. The rest of McCay's characters, from Sammy Sneeze to The Pilgrim to Little Nemo were blank slates. McCay's focus was on his art work. In "Krazy Kat" however Harriman however created a stable of characters who had distinct (if limited) personalities.

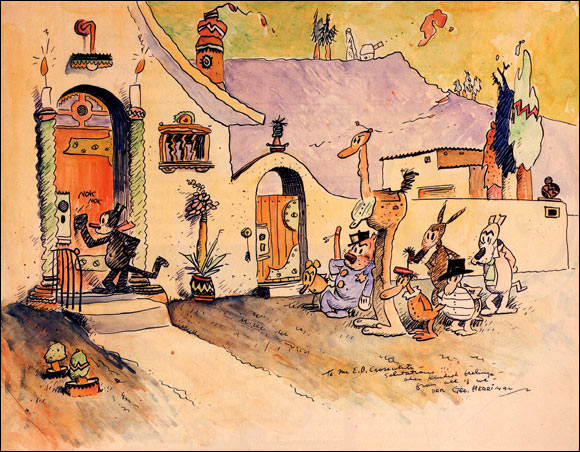

More groundbreaking in "Krazy Kat" was the strip's visual style. In earlier strips the animal characters were drawn in a fairly linear and detailed style. However Harriman developed a style that was more stylized and minimalistic consisting of blocky shapes and simple colours while still remaining recognizable as the animals they represented. His characters while simple also were able to show facial expressions and emotions. This style was radically different than the conventional styles but would become highly influential on future cartoonists like Walt Disney whose early "Mickey Mouse" strips and toons greatly resemble "Krazy Kat".

Besides the characters, the backgrounds were equally groundbreaking. Previous strips used backgrounds that had conventional background scenery. Winsor McCay had broken that mold with some of his dream-like fantasy backdrops but Harriman's stylized backdrops were different in their stark simplicity and beauty. Heavily influenced by the desolate plains of the Southwest in Arizona and New Mexico (where he would later move) with their flat featureless landscapes dotted with oddly shaped mesa rock formations and lonely cacti and sagebrush. Harriman's backgrounds offered an other-worldly dreamscape populated by strange characters. Once "Krazy Kat" became popular enough to score a prized spot in the colourized weekend editions his strips became even more dreamlike as Harriman would colour the starless skys jet black, orange or yellow with occasional smudgy clouds or a misshapen moon. The influence of these expressionistic backgrounds can be especially seen in those of the "Roadrunner", "Pink Panther" and "Rocket Robin Hood" cartoons and comic strips like "Broom Hilda" and "B.C." and the works of Dr Suess and Ralph Bakshi.

As with Winsor McCay, the question of where George Harriman took his influences from is an interesting one. The Expressionist and Cubist movements were contemporary but it's unknown if Harriman, with little advanced art training, had any exposure to these avant garde European schools at this time. Many have noted the resemblance of Harriman's backgrounds with the paintings of Salvador Dali, but Dali was still a child at this point. Harriman seems to have worked out his own style independent of higher art schools although his background showed he was well aware of the work of other cartoonists, including no doubt McCay. Harriman did not have the draftsmanship skills of McCay or his meticulous attention to detail but his ability to work fast on multiple projects and the rather improvised nature of the early "Krazy Kat" strips may have led him to work out a simple, uncluttered response to McCay's dream world that he then quickly expanded on. The addition of colour added to his distinctive style.

The weird and unique strip became a success for Harriman, giving him at last a long-run strip. Although the strip was too weird and difficult to become hugely popular with the general public it did gain a loyal and influential following amongst artists and intellectuals. The combination of the strip's outlandish visual style, odd verse-like dialect and charming if repetitive love triangle earned the strip praise from the likes of H.L. Menken, e.e. cummings, Will Rogers, Gilbert Seldens, F.Scott Fitzgerald, Walter Lippman, Robert Benchley, Ezra Pound, Lord Buckley, E.B.White, Frank Capra and Harold Lloyd. President Woodrow Wilson was such a devoted fan that he would interrupt cabinet meetings to read the latest strip which he also had sent to him while he was in Europe in 1919. In 1921 composer John Alden Carpenter even wrote a "Krazy Kat" ballet which was actually performed. Earlier the then popular Ragtime banjoist Fred Van Epps recorded a soundtrack to a Krazy Kat cartoon (more on the Krazy Kat toons below). The most important fan (from Harriman's point of view) was publisher William Randolph Hearst who gave Harriman a lifetime contract for the strip to be carried on all papers which he honored for over twenty years until Harriman's death.

FRED VAN EPPS ~ "KRAZY KAT GOES A WOOING";

ANIMATED ADAPTATIONS;

By 1909 Winsor McCay had already done pioneering work to make animation practical. There had been crude experiments in animation for years with only limited results. It was McCay who developed the basic techniques that are still essentially used today, at least until computer animation was invented. McCay's cartoons were fluid and lifelike to an amazing degree and led to the birth of a new medium which he encouraged as he happily shared his new techniques rather than seek a copyright and issue lawsuits as Edison surely would have. Accordingly in 1916 the first "Krazy Kat" cartoons were made by Hearst's Vitagraph News Pictorials, a studio that normally made newsreels. They had limited involvement from Harriman himself and were actually animated by either Frank Moser or Leon Searle. Moser was a trained artist originally from Kansas who had worked as a newspaper cartoonist in Des Moines and New York. Searle was another newspaper cartoonist who worked for Pulitzer in New York and Philadelphia. Neither had any animation experience, although at that point neither did anybody else.

"KRAZY KAT GOES A WOOING" (1916);

These cartoons kept the basic look and characters from the original strip along with the love triangle however simplified to fit in with their short (approx 3 minute) length. The characters looked exactly as they had in print. However the toons lacked the distinctive backgrounds of the strips, especially the colour strips. The toons also lacked much of Harriman's distinctive dialect verse. The stories relied mostly on slapstick which was typical of comedy shorts of the time although they did try to maintain some of the basic feel of the original strip. However the most glaring shortcoming of these strips is the animation itself. Frank Moser simply did not have the McCay's talent as an illustrator or an animator. McCay's animation is fluid and lifelike while Moser's is crude and jumpy. To be fair McCay's techniques were very new and Moser had little time to learn them, these toons were also probably done rather quickly, especially compared to McCay's exacting work. With his flowing animation and legendary attention to detail Winsor McCay took over a year to do his masterpiece "The Sinking Of The Lusitania" while Moser did the entire "Krazy Kat" series in less time. The time and work McCay spent on his toons in fact led directly to Hearst (who also employed McCay) to eventually ban McCay from further animation work as Hearst felt it was distracting him from his newspaper work, much to McCay's annoyance. While the Moser strips are clearly inferior to McCay's work it must be said that their simple visual style was more influential than McCay's more complex and difficult works at least in appearance if not animation technique. The "Felix The Cat" cartoons which appeared in 1919 produced by Pat Sullivan looked exactly like "Krazy Kat". Warner Brothers would follow with their own similar series,"Bosco" in 1927. When Walt Disney began the first Mickey Mouse cartoons a decade later the "Krazy Kat" resemblance was obvious. Frank Moser would go on to an influencial career of his own as one of the founders of the successful Terrytoons Studios in 1929 with characters like Heckle & Jeckle and Mighty Mouse. He also became a respected painter. Moser died well into the TV era in 1964. Leon Searle was less fortunate, he made over a dozen "Krazy Kat" toons before dying suddenly in 1919 aged only 38.

"KRAZY KAT; BUGOLIGIST";

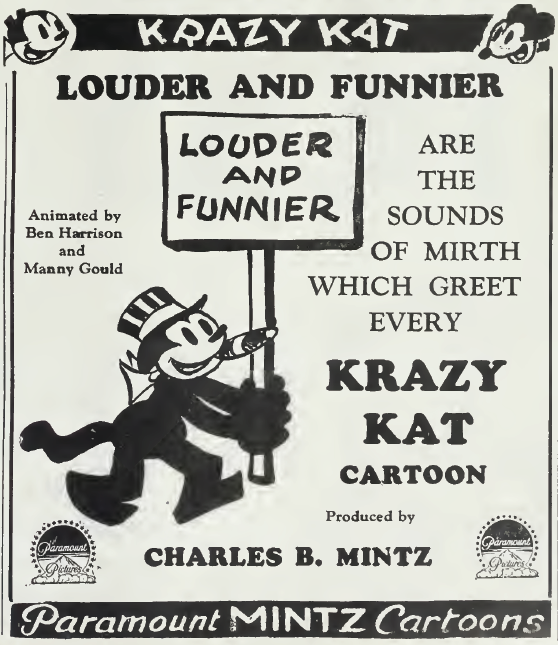

In 1925 Bill Nolan, a respected animator who had worked on "Felix" took over for a new series of "Krazy Kat" toons. Unlike Moser's toons which kept true to Harriman's originals, Nolan's toons in fact resembled "Felix" both in appearance as well as in discarding the basic plot-lines and dialect in favour of a pure slapstick approach. They also dispensed with Harriman's iconic backgrounds in favour of more conventional settings. These toons were successful enough to continue (under different animators) until 1940. Some of these toons were quite imaginative visually and even surrealistic but did not have Harriman's distinctive poetic doggerel. Harriman had nothing to do with these toons and probably did not approve although he likely did appreciate the royalty cheques. Nolan would go on to work with Walter Lanz on the "Oswald The Rabbit" series. He died in 1954.

"KRAZY KAT AT THE CIRCUS";

George Harriman died in 1944 and his remaining finished strips were published for a few more weeks before the strip was discontinued. While it was not uncommon to continue strips after a cartoonists death, Hearst felt that Harriman's unique style was irreplaceable, although it's also worth recalling that the strips were not really money makers anyway. Still their influence was acknowledged. The now famous Walt Disney wrote Harriman's surviving daughter a letter in which he praised George Harriman as one of the founders of modern cartooning and animation and a personal influence. (he also did the same with Winsor McCay's son)

KRAZY KAT; "BARS & STRIPES";

In 1962 King Features made a series of "Krazy Kat" toons for television. These toons made an attempt to return to the basic appearance of the Harriman originals. They were proceeded in the fifties by a comic book series put out by Dell Publications which had little to do with the original strip and was instead a basic mainstream animal strip which Felix had also become. These comics were popular enough to stay in print until the 1960's by which time they were taken over by Gold Key Comics. These fifties and sixties versions helped to introduce "Krazy Kat" to the psychedelic generation and cartoonists like Ralph Bakshi ("Fritz The Cat"), R. Crumb and Matt Groening who's "Simpsons" would have the ultimate "Krazy Kat" parody in it's "Itchy & Scratchy" characters. While "Itchy & Scratchy" are often seen as taking the likes of "Tom & Jerry" and the likes, which they are, they also incorporate elements of the dysfunctional relationship relationship between Krazy and Ignatz. No matter how many times Itchy the mouse (note the similar name) explodes, disembowels, decapitates, immolates, etc, etc Scratchy the Cat, Scratchy still loves Itchy and stands by his mouse. Some Kats never learn.

KRAZY KAT; "THE HOT-CHA MELODY";