"CONEY ISLAND AT NIGHT" (Directed by Edwin S Porter, 1905)

Documentaries are the shy, nerdy little sister of films. All the fame, fortune and glamour goes to her pushy, glamorous feature film sisters but docs were the original movies. The first films were simple short scenes of real life; street scenes, trains rushing by, people at work, etc. The term for these films was "Actualities" and they made no attempt at telling a story, the director simply pointed his camera at something or somebody and cranked away for a few moments. These were easy and cheap to make and were popular for the first decade of film in the 1890's until the early novelty of film wore off and audiences started demanding proper stories and recognizable stars.

"HAARLEM" (1922);

Eventually filmmakers would take things more seriously and add more location shots and edit together more scenes to give a more varied portrayal of a city for but the resulting films were decidedly conventional both on their camerawork and the scenes they chose to show. These films were more like tourist travelogues with no attempt to tell any real story and they definitely would not be showing the skid row.

"TORONTO; CANADA'S QUEEN CITY";

Within a few years documentary filmmakers in turn figured out how to tell a personal story with real people and even have a hit film as with Robert Flaherty's "Nanook Of The North" (1922) and "Moana" (1925). These were critical and audience favorites for which the term "documentary" was coined to differentiate from the earlier short crude actualities to feature films that told a proper story. Flaherty prefered exotic locations and vanishing civilizations and fairly straight forward camerawork and storytelling but there was another group of filmmakers who would focus on settings closer to home in the bustling metropolis and more artistic and kinetic cameras and editing influenced not only by film but also by art modern movements like Impressionism, Futurism, Cubism, Constructionism and Realism to use documentary film in a way that would tell a story about life in the city without having a real plot or characters. These films would rely on camera work of multiple images and editing to imply a narrative that would flow more like a symphony than a traditional story.

"MANHATTA" (1921)

It's notable that first of these city art films was made not by a film director but by a painter who was more interested in exploring the look and atmosphere of the city than it's actual people or in telling a story. Charles Sheeler (1883-1965) was an American painter based in New York known for his very precise landscape paintings of the industrial city. In 1921 he decided to try film as a medium and teamed up with photographer Paul Strand (1890-1976) to make "Manhatta" (AKA "New York The Magnificent") a short film in which they shot various scenes in the city intercut with lines from Walt Whitman. The film starts in the morning at the harbour with incoming ships, moves inland to show some construction workers, followed by shots of the canyons of towers shot from high up, shows some scenes of trains and railyards, the Brooklyn Bridge, then back to the harbour for the sunset. The film shows little interest in actual people and in virtually every shot of people they are invariably shot from far away and they are all faceless and anonymous. The film is also odd in what else it leaves out as in a film about Manhattan it has no shots of the Statue Of Liberty or the lights of Broadway.

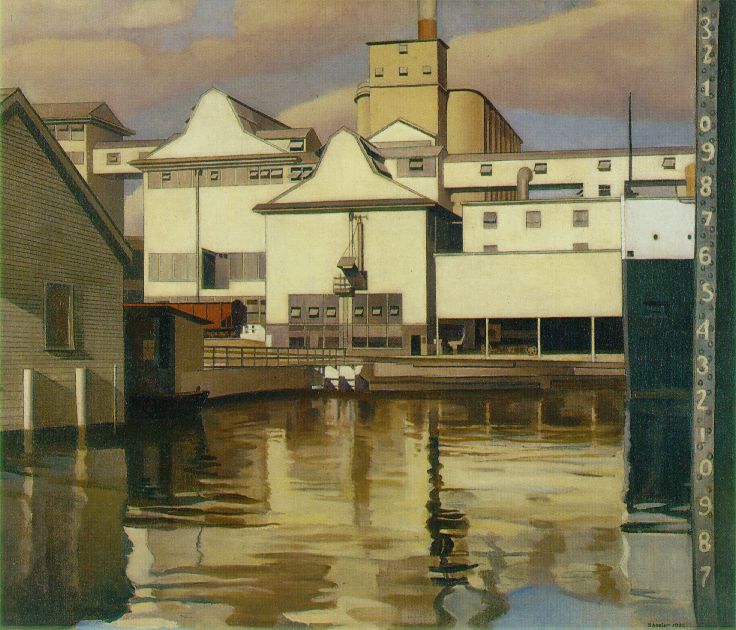

A CHARLES SHEELER URBAN PAINTING

Although as a painter Sheeler was part of an urban Realist school called Precisionists rather than an Impressionist he shows an Impressionist's fascination with the smoke wafting from the forest of chimneys in many shots and other textures. The film has no discernable plot, subtext or point of view, it merely passively observes from a distance. Although the film has no obvious politics Strand was an active Communist and union man and it's probably at his insistence that a few shots show working men as they dig ditches and work on skyscrapers as these are literally the only shots with people where they are shown at anything other than from a distance either from behind or above. Comparing this film with Sheelers's paintings of New York likewise shows a great attention to detail of various buildings but few if any people at all. Strand's work however was always focused on workers. This was Sheeler's only film although Strand would work on a few left wing pro-union and anti-facist documentaries in the 1930's and 40's. In 1949 he moved to France for the rest of his life. The original negative of this film is considered lost with only a single 16mm print surviving which was more recently restored.

"MANHATTA" (1921);

Note; For this silent video I added a soundtrack from the Contemporary Jazz Quintet (1967) with the artsy, moody, cacophony seeming right for the film.

==============================================================

"Paris; Nothing But Time" (1926) by Brazilian director Alberto Cavalcanti is considered a City Symphony but there are significant differences between this film and the others in this genre. Like the others it shows a day in the life of the city however this is not really a proper documentary as while it does have many scenes that are no doubt genuine shots of city life there are many more that are clearly staged including with actors. In fact this film has more in common with the related genre of "Street Films", mostly made in Germany which dealt with the working class denizens of the city and were shot in realistically gritty street settings but used scripted stories with actors. Examples would include "The Street" (1923), "The Joyless Street" (1925), "Tragedy Of The Streets" (1927), "Asphalt" (1929) along with the American DW Griffith's "Isn't Life Wonderful" (1924). I will deal with these films in another article.

"Nanook Of The North" director Robert Flaherty (1884-1951) took time out from his usual rural and wilderness subjects to try his hand at an urban setting in New York with "24 Dollar Island" (1927). This film is more straight-forward documentary and less artistic film compared to "Manhatta". The film opens with an explanation of the founding of the city with the Dutch "buying" the island from the natives for $24 (hence the title) done in the dry style of a later classroom educational film. Like "Manhatta" the film starts and ends at the river and harbour, shows a couple scenes with construction workers and includes a lot of shots of skyscrapers. Flaherty does not have Sheeler's painterly interest in dwelling on the look and feel of the billowing smoke and textures of the buildings and there are no really memorable shots here, indeed there are no shots here that couldn't have also been in "Manhatta". Another difference is that while "Manhatta" (and subsequent City films) present a day in the life of the city from morning to noon, this film had no structure and simply meanders back and forth between the harbour and city. Again while this film is about New York it avoids it's most famous landmarks. Both films show little interest in actual people rather than the buildings, ships, bridges and machines that surround them which is odd since while Sheeler in his previous paintings showed a similar obsession with objects rather than the almost entirely absent people who live and work in the city this was definitely not true of Flaherty whose classic films "Nanook Of The North" (1922), "Moana: A Romance of the Golden Age" (1926) and "Man Of Aran" (1936) were explicitly about the conflict of man trying to survive against a harsh nature. Here man is incidental and faceless. Ironically while Flaherty was the experienced director and Sheeler and Strand were amateurs his film comes off as a perfunctory copy of "Manhatta" with less cohesion and artiface. This may be because this film was privately financed and this may have just been a quick job for him rather than a project he gave much thought to unlike his other films which he worked on for years.

"24 DOLLAR ISLAND"; (1927);

=======================================================

JORIS IVENS

Joris Ivens (1898-1989) was a Dutch filmmaker who, like Paul Strand, started as a photographer before making short films that explored photo techniques to create Impressionistic docs about everyday subjects. The most notable of these early silent subjects "Die Brug" ("The Bridge"), in 1928 was a study of a new vertical lift bridge in Rotterdam that explored the mechanics and structure of the bridge in the kind of detail Charles Sheeler used in his paintings. Like Sheeler his film is focused entirely on the objects and structures to the exclusion of people. There are only three people fully visible in the film; Ivens himself (with his face obscured by a camera) and workman climbing down a ladder (whose face we can't really see) and the bridge master in charge of raising and lowering the bridge, he is literally the only person whose face we see. For the rest of the film is focused on machinery, the struts, gears and girders of the bridge itself, the train rails, the train approaching the bridge, trucks crossing, barges passing underneath, all shot in close up gleaming detail. The Futurists of the 1910's shared a fascination with machinery which may have influenced Ivens and Sheeler but they were also influenced by Cubism showing their gears and girders in abstract forms unlike the painstaking details shown by Realists like Ivens and Sheeler/Strand. The Futurists were also obsessed with movement, often showing their subjects blurred by a whirl of dramatic activity while Iven's machines moved slowly and magistically.

Note for this film I added a soundtrack from the early eighties Sheffield Post Punk Jazz group Bass Tone Trap with it's moody, droning percussion fitting the film.

"DIE BRUCKE" (1928);

The next year Ivens did another short urban study with "Regen" ("Rain"), once more in Rotterdam. This time the focus was not on a specific structure but showing parts of the city during a rainstorm. This film is much more Impressionist in it's lingering shots of gleaming streets, the texture of puddles, the play of rain drops on the canals and a forest of umbrellas. Once again the film starts at the harbour and some boats sailing in. Unlike the obsession with modern machinery there is a shot of the rooftops of what is presumably one of the poorer areas of the city which looks rather medieval and oddly like a set from a German film like "Der Golem", followed immediately with a shot of a modern ship sailing in which in turn has a horse and wagon passing on the pier in the other direction followed by more boats picking up speed. After more sleek modern speeding boats there is another shot of old buildings abutting the river with a man in a small punt boat rowing at a glacial pace. As the city starts it's day with shots of opening windows the clouds darken and the rain starts. Once again people, although present, are largely secondary. Shot from a distance or from above with only a man looking up at the clouds and dashing across the street and a woman waiting to board a tram being the only shots where people's faces are clearly shown, albeit briefly, and that is only to show their reactions to the rain which is the real character of the film. As the rain picks up we move away from the river's edge to the rainswept streets and wet cobblestones with cars and people rushing past although the river is never far away. The rainfall intensifies then slackens off before coming to an end by the evening.

"REGEN" (1929);

(soundtrack from Industrial/Sound Collage band Nurse With Wound)

Here we have all the elements of a proper City Symphony as we see a day in the life of the city with plenty of movement. By comparison the previous films were focused almost entirely on slow, lingering shots of buildings and structures, here there is a busy, lived-in city even if we learn nothing about it's people. Like Sheeler, Ivens focus is still on objects rather than people. One early shot of the rooftops of the city's Old Quarter actually looks like a studio model Ivens' two films are still essentially Impressionist studies but this one does show a living, breathing city in a way that "Manhatta" and "24 Dollar City" do not.

While these films don't have any paticular story or subtext Ivens, like Strand, was a committed Marxist who would later make porpaganda films in the Soviet Union and China as well as for anti-fascist film during the Spanish Civil War. If his two city shorts could be faulted as having little human content that would not be true of the rest of his work. During World War Two he would make propaganda films for the USA (at the invitation of Franklin Roosevelt) and Canada. After the war during the Red Scare he would find himself blacklisted and would return to Europe where he would continue to work into the 1970's including films about the Indonesian fight for independence from Holland and the Vietnam War. In the 70's he returned to China and spent six years making "How Yukong Moved The Mountains", a documentary which is considered the world's longest at over twelve hours long. Shortly before his death he won the Golden Lion Honorary Award at the Venice Film Festival and the Order of the Netherlands Lion with the old Marxist being feted by the Dutch King, Ivens died months later at the age of 90.

================================================

"Berlin; Symphony Of A Great City" (1927)

Previous films had shown how the city could be shown as not only a setting but almost a character itself but none of these films had either the breadth or scope to fully explore the idea of a truly living, breathing city. Previous such films had been shorts, "Berlin; Symphony Of A Great City" would be the first feature length City Symphony. The idea for a full length film exploring a day in the life of Berlin told through candid shots of street life came from Carl Mayer (1894-1944), a screenwriter who had worked on four films with director FW Murnau including "The Haunted Castle" (1921), "The Last Laugh" (1924), "Tartuffe", (1926) and "Sunrise" (1927) as well as horror films "The Cabinet Of Dr Caligari" (1920), and "Nights Of Terror" (1921), the historical epic "Danton" (1921) and "Erdgeist" (1923) a version of the Lulu series (which I've already written about here). By 1925 Mayer had become bored by the restrictions of fictional narratives and frustrated by the interference of movie studios who had changed the endings of "Caligari" and "The Last Laugh" over his objections. One day while at lunch observing the hectic street life of Berlin he got the idea that one could tell a story of a day in the life of the city entirely through candid shots of the city itself and without using a script, artificial sets or actors, and he began sketching out a scenario. Since Mayer was a writer rather than a director he contacted innovative cameraman Karl Freund (1890-1969) who had also worked on "The Last Laugh" and "Tartuffe" along with horror films "Der Golem" (1920), "The Janus Head (1920 w/ Murnau) and Fritz Lang's "Metropolis" (1927). Freund had also grown frustrated by the limitations of German filmmaking where most German films of the era were shot entirely indoors, and took on the challenge of being able to covertly film the city's goings on while doing so in an artistic way. To do so he devised hidden cameras that could be concealed in vans or wagons and even a small camera disguised in a briefcase and set out to film the city working on suggestions from Mayer as well as shooting scenes that suggested themselves to him on the fly. Freund and Mayer always insisted that the people they shot were unaware of the camera and no shots were set up or rehearsed. Freund embraced the theme of candid filmmaking as; "It is the only type of photography that is really art. Why? Because with it one is able to portray life."

After shooting days of film the job of editing the mass of footage into some kind of somewhat coherent narrative was handed to director Walter Ruttman (who I've written about here). Ruttman (1887-1941) was not a conventional feature film director, he had come out of the same Dada scene as Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling and had made several art film shorts that used lights, shadows and shapes in what he called "Opuses". From these obscure starts he then branched out becoming a pioneering animator having made several short corporate promotional films. Ruttman's willingness to experiment made him an interesting choice for an unconventional project but he had also shared with Mayer an interest in approaching such a film like a musical composer rather than a playwright. Stating; "Since I began in the cinema, I had the idea of making something out of life, of creating a symphonic film out of the millions of energies that comprise the life of a big city."

WALTER RUTTMANN

Instead of relying on dialogue the narrative would be presented through "movements" like a symphony rather than through acts as in a play. Themes would be presented and implied rather than explained and would ebb and flow in a "natural" way rather than a narrative way. The concept of "Visual Music" had been suggested as early as 1924 with Eggeling's pioneering Op-Art short "Symphonie-Diagonal" then being picked up by his friend Hans Richter for his series of Op-Art shorts "Rhythmus 21", "Rhythmus 23" and "Rhythmus 25". Walter Rutmann would pick up on this with his equally abstract "Lichtspiel; Opus 1" (1926) and later films "World Melody" (1930) and "Wochenende". FW Murnau had actually presaged this theme with the full title of his iconic 1922 horror classic "Nosferatu; A Symphony Of Terror". Keeping the concept of "Visual Music" in mind Ruttman set to work with composer Edmund Meisel who would also be commissioned to write a full score for the film. Ruttman would be credited as the film's director although Freund had already shot all the footage before Ruttman came on to the project.

"BERLIN; SYMPHONY OF A GREAT CITY" (1927)

Once again we start with a shot of water but as Berlin is not a port city we quickly shift to shots of a train rushing into town which sets a different tone from the previous films. Where Paris, Rotterdam and even New York were presented as dreamy Berlin will be a beehive of activity and alive with movement. At first as the train enters the city we literally do not see a single person, the train seems to be alive itself and the city streets are eerily deserted as in a modern post-apocalypse movie. It is early dawn and still dark out and slightly misty. Right away we are informed that this view of the city is not going to be a glamorous travelogue by a shot of a grimy sewer grating and shots of the sewer tunnel itself which does not have the ethereal shafts of light the Paris sewers did. There are shots of high rise buildings, power lines and boiler pipes looking coldly utilitarian unlike the gleaming gears of Joris Ivens. The only signs of life are a single piece of stray paper drifting down the street and the only humans we immediately see turn out to be department store mannequins. Finally we see an actual human aimlessly walking his dog and then a curiously large cat out for a morning stroll. Slowly they are joined by more people wandering about including a couple of cops. After a shot that shows a train dramatically creeping towards the screen head-on so it looks like some kind of living monster, the city starts to come to life as we see more and more people and they are moving faster with a sense of purpose. Soon the streets will be full of people and vehicles. There are shots of factory gates along with some cows being herded through the streets to show that these people are going to work. Just what the work is like we can see as Ruttmann is as fond as Joris Ivens of showing montages of heavy machines grinding and whirring away with little human involvement except to feed and tend to the machines, a theme also explored in "Metropolis" the same year. However this cold edge is softened with a human touch as we start to see stores open, street cleaners and some young girls going to school. Besides working people we also see the wealthy climbing into limos, taking a morning horseback ride in the park, checking into a luxury hotel. Although the film obviously has no real plot it does divide into acts to separate into times of the day; morning, afternoon etc. By mid-day we are seeing shoppers and more department store windows with animated dummies. A fight breaks out between two men before a cop shows up to seperate them. The Circle Of Life; A bride arrives for her wedding, an old woman slowly picks her way up some church steps, a horse is apparently struck by a car and later an elegant horse drawn hearse drives by. At lunch everybody breaks; workmen at their site, white collar workers at lunch counters, the bored wealthy being served obscenely ornate meals at lush restaurants by an army of waiters and even the horses and zoo animals have their meals. For the fourth act we are wrapping up the work day and switching over to leisure with a roller coaster ride and a fashion show but this is undercut with a scene where a distraught woman jumps from a bridge into the river and drowns and the zoo animals getting increasingly agitated as a storm whips up and fire engines race by. However the storm quickly blows over and Berliners go back to enjoying themselves as work lets out going to the parks, racing boats, cars, bikes, dogs, horses, pigeons and people. Playing golf, tennis, hockey, and polo. For act five it is nightfall as the lights come on and we see cars speeding through demp, darkened streets lit up by neon signs. By the evening it's off to dances, movie theatres (one showing a Tom Mix western and another a Chaplin film for which we see his legs shuffle past, it's probably "Gold Rush"), and Berlin's famous nightclubs and cabarets. As the city parties into the night fireworks blaze and a lone spotlight pierces the darkness. Finis.

=================================================

After the earlier films set some of the template this is one of the two definitive City Symphonies, the other being the Soviet "Man With A Movie Camera" which we will deal with shortly. Previous films were either too short ("Manhatta"), or too narrowly focused (Iven's two shorts) or both. This time Ruttmann, Mayer and Freund had a full canvas and a fully realized concept of telling a day in the life of a city with imagery and a more vague but workable idea of approaching the story as a symphony with movements albeit presented here as "akts" in deference to film conventions. "Berlin" would inspire a few immediate follow ups and can also be seen in the 1982 film "Koyaanisqatsi" directed by Godfrey Regio with soundtrack by Philip Glass.

However while largely considered a classic the film has also been the subject of debate starting with it's own creators. Once the film was handed over to Ruttmann for the mammoth task of editing Carl Mayer had no further say in the project and as with his previous experiences with "Caligari" and "The Last Laugh" he was unhappy with the results and insisted that Rutmann had not fully understood the project. Some later critics agree (including Dziga Vertov director of the later Soviet film we will soon see) with the main criticism being that Ruttmann's approach was too focused on the visuals of trains, buildings, machines etc and flashy visuals at the expense of the actual people who are largely anonymous as was the case in the previous films. They found his Berlin to be cold and remote. Mayer had wanted to focus on the people and Ruttmann had focused on surface visuals. In the light of a past century is this critique fair? In all his previous (and subsequent) films Ruttmann had been a visual artist obsessed with form and movement while Mayer had been a screenwriter naturally focused on stories. But it is hard to see how Mayer's concept was fully workable without some cheating anyway as turned out to be true.

Although Fruend and Mayer always insisted the entire film was shot with candid cameras and without the knowledge of it's subjects this is clearly not entirely true as the woman's suicide sequence is certainly staged and even requires a closeup shot that can not have been shot from afar. Likewise the scene of two men getting into a brawl was shot from two different angles and was likely staged as well, although the crowd that gathers, and even the cop who breaks it up may not have known this and are probably genuine. In a more subtle scene which may or may not be staged a man and woman window shopping coming from different directions appear to flirt and go off together. There are a few other shots that require a close up shot or angle that seems unlikely to have been truly candid, especially shots of a dance orchestra and a jazz band, and a few others where subjects appear to glance into the camera. The bulk of the film however is undoubtedly what it claims to be. At this point it is unknown whether these shots were all done by Freund or if Ruttmann went back and shot a few scenes himself which if true would have slightly violated the scenario set down by Mayer which would have added to his annoyance. Either is possible.

Ruttman, a former animator, inserts some trick photography shots showing spinning typewriter keys, montages of newspapers and shots of people yelling over the phone with shots of dogs fighting. Either Freund or Ruttmann share Iven's fascination with trains and the film is chock full of trains speeding back and forth. Shot from every angle inside and out as well as shots from the train. He also takes obvious pleasure in showing department store dummies who seem more animated than many of the actual people. While there are a few indoor shots of factories, a hotel lobby, a movie theatre and nightclubs the bulk of the film is focused outside, on the streets of Berlin. Although Mayer and others have faulted Ruttmann's focus on machines and objects over people, his Berlin is shown as a thoroughly modern city as with Sheeler's New York and Iven's Rotterdam and unlike the subsequent Paris films we shall see, there is no nostalgia or romanticism here.

There are only the barest hints of the political upheaval for the Weimar years as a troop of armed soldiers march by a couple times and a communist street speaker harangues a crowd (we can assume they're communists as many in the crowd appear to have red flags and there are no Brownshirts in sight) before being arrested by the police. In fact although within six years the Nazis would take control there are no obvious Nazi figures to be seen anywhere although it is worth noting that Berlin was never a hotbed of Nazi support. There is some political subtext as are a few shots of poor and unemployed men and a shot of a wealthy man discarding a cigarette and a vagrant picking it up. Notably we only see the rich man's expensive shoes but not his face while we do see the vagrant's. After the scenes of wealthy being fed overstuffed meals we see much of the food tossed out and the poor picking through it. Notable that while the film is shot in Berlin there are a couple of shots with black citizens going about their day without anybody giving notice; a black man dressed in business casual in the street chatting with two other white men, an African in more traditional tribal gear boards a trolly (worth recalling that Germany had African colonies up until WW1) and later a black vocal quartet plays to an appreciative crowd, there is also a shot of a group of elderly Jewish men taking a stroll deep in conversation. A brief scene in which a policeman stops traffic to escort a child across the street has been cited as showing the police as keeping order in the chaotic city and indeed this scene seems lifted from the previous Street Drama "Die Strasse" (1923) which has an almost identical scene but in that film the scene is highlighted and is in the context of a greater story about criminals which is not the case here and the police are not a paticularly important presence. Berlin is not shown as a potentially Nazi city but is instead a pluralistic modern one, if hectic. Despite these hints it is true that the film has little political context for a time that was infamously the most politically significant in modern times. Soon a Soviet filmmaker would take this colour pallet to make a significantly different and more political film.

=====================================================

"ETUDE DE PARIS";

Before going to the USSR there would be an interlude. If Berlin could have a tribute to it's greatness then obviously Paris must have one too, "Etude De Paris" (1928) is that response. Directed by Andre Sauvage (1891-75), and set in Paris.

"ETUDE DE PARIS" (1928);

(Soundtrack from Brian Eno)

Once again the film starts at the water, in this case the River Seine, and spends time with the various boats and horse wagons on the river bank before heading to shore. Since this is Paris Sauvage gets to use the tunnels that are part of the legendary Paris Underground which leads to a striking shot with the canal-boat travelling through the arching tunnel while shafts of light shoot down through the skylights in what is easily the best sequence in the film. Taking a cue from Ivens two films, Sauvage takes some time to dwell on shots of water and the gears for the canal locks. Unlike Ivens and Sheeler who avoided shooting any recognizable buildings or structures Sauvage is in Paris and thus is not going to ignore getting shots of the Eiffel Tower, Notre Dame or Moulin Rouge. Also unike Ivens and Sheeler he is more interested in getting shots of actual people going about their day. There is even an odd sequence in which a young couple come down opposite ends of a double staircase, look at each other sadly then walk away, presumably lovers on a breakup. Later on they seem to reunite and sit together on the river bank but we never see them again or learn anything about them. It just seems to be a throwaway scene, charming but out of place with the rest of the film since it was clearly staged while the rest of the film are candid shots of the general public. While Sauvage takes more interest in people than Ivens and Sheeler do in their films, this city is full of people compared to Sheeler's rather arid New York, he does not have their eye for detail or Ruttmann's sense of narrative focus. In fact much of the film comes off as a travelogue. Not necessarily a tourist friendly one however as he does show the seedier and grimy parts of Paris with noticeably rundown buildings, brokedown unemployed men sitting dejected and alone and what appears to be a hobo shantytown that looks like it belongs in a Latin American Barrio. On the other hand even at its worst this Paris is not as grim and seedy as in Alberto Cavalcanti's 1926 film "Paris; Nothing But Time". Ultimately however this film lacks the sense of purpose or artistic vision of Ivens or even Sheeler as well as their painterly focus on Impressions which is odd as he was actually a painter before he was a filmmaker. He clearly lacks the energy and eye for detail of Ruttmann, Mayer, and Freund's film. Their Berlin is a frenetic beehive of modern activity, by contrast Sauvage's Paris is rather sleepy and dreamy which is probably a not entirely accurate comparison. It is essentially a collection of scenes with no underlying theme or subtext. There is another important difference between them; in the films of Sheeler's New York or Ivens Rotterdam, they avoided any landmarks that would clearly identify them as New York or Rotterdam. They can thus represent any modern western city of the era, at least in theory, while Sauvage's Paris can only be Paris.

Andre Sauvage made only four films, three of which were silents. Then after a few years break he filmed another sound doc in "La Croisiere Jaune" (1934) which was about a gruelling auto race across Asia funded by automaker Andre Citroen. However Citroen was dissatisfied with the results and took the film out of Sauvage's hands and gave it another director to edit. Sauvage never made another film and instead retreated to the countryside where he occupied himself with painting and writing.

===========================================

Another Paris response to "Berlin" was "Harmonies de Paris" (1928), directed by Lucie Derain (1902-1967?), about whom little is known. Her real name was Lucienne Dechorain and she worked as a writer and editor for various film magazines and also worked on a number of films also as a writer before making trying her hand at directing in 1927 with a short film "Désordre" a film described as a "montage art film" that got some positive notices but which is now lost and following it up with "Harmonies De Paris", another short film meant to be shown along with another art film directed by Rene Claire. Derain was quite open about basing her film on Ruttmann's "Berlin" even down to adopting the basic structure albeit in less time as well as using a musical term to describe it. Since this film is less than half the length of "Berlin" is a "Harmonie" rather than a "Symphony".

"HARMONIES DES PARIS" (1928);

Right away this Paris announces it's different from Sauvage's Paris by having the entrance to the city not through a slow river boat but via the most modern of vehicles, a plane. Instead of a leisurely journey along the river bank we get an aerial view of the city. When we do see riverboats they are not the slow ancient riverboats being paddled or towed by horses but modern steam powered, we also get trains albeit shot with less of the obsessive attention to gears and wheels than Ruttmann or Ivens. Like Ruttmann we seem to start early in the morning with little traffic although the sun is fully out (she presumably shot some of this on an early Sunday) unlike the overcast Berlin and Rotterdam. We see the rushing commuters, busy traffic and bustling markets. While the streets of Paris are shown as wide and modern compared to the rather more crowded Berlin we do spend a little time in the cramped Old Quarter but it is clearly not the focus of the film. Of course this being Paris Derain is also not going to pass up shots of Notre Dame, the Arc De Triomphe and the Eiffel Tower which somewhat takes away from the sort of narrative flow of "Berlin" or "Regen" in favour of becoming a travelogue. This film was meant to be shown in Britain as well as France so that may have been intentional. One notable difference with "Berlin" was when Ruttmann showed scenes of the upper crust s dining and parading their wealth he did so with some implied disapproval contrasting those scenes with those of poverty while Derain shows a boulevard of expensive shops she adds in the inter-title "Elegance!" with no implied disapproval or scenes of poverty, although she does then pivot to showing some construction workmen and dock workers. For that matter, Ruttmann had no inter-titles at all aside from those announcing a new "akt" but Derain, being a writer herself, just could not resist adding some even if they are not needed. Derain does toss in a few trick shots including a distorted shot of the Stock Exchange which implies instability but there is no other context provided and uses montages of trains and factory workers similar to Ruttmann's to show the hectic speed of modern life but again there is little context, in fact this sequence leads into a segment entitled "Nocturne" showing scenes of the glowing Paris nightlife albeit with far less than we got of Berlin's. Unlike "Berlin" we do not actually end there however and instead seem to go until the following morning with a lazy stroll in the park in the sunlight.

Derain's Paris is ultimately more focused than Sauvage's although less so than Ruttman's "Berlin" or Iven's "Regen". We don't get any scenes as evocative as Sauvage's canal boats passing through the underground, it is a more modern and real portrayal and a worthy response to Ruttmann's film given the limitations of it's shorter length and scope. Derain was supposed to follow this film up with one about Rouen titled "Rouen, Ville Sonore" in 1929 but it has also not survived and it is unclear if it was actually even made. She made no other films leaving "Harmonies Des Paris" as Derain's only surviving film. She returned to a succesful writing career into 1940 until the Nazi occupation. She resumed her career as a writer and editor of a film magazine until 1948 and seems to have retired or dropped out of sight aside from a listing in a who's who of French film in the fifties (as a writer) and is believed to have died in the sixties almost completely forgotten as a director.

LUCIE DERAIN

=========================================

"Man With A Movie Camera" (1929) is, along with "Berlin" the other acknowledged classic film of this genre and the two films are always compared with most critics seeming to prefer the latter film. Directed by Soviet filmmaker Dziga Vertov (1896-1954, real name David Kaufman) working with his cameraman brother Mikhail Kaufman (1897-1980), and edited by his wife Yelizaveta Svilova (1900-75). Vertov and his brothers were part of a group of young Marxist documentary filmmakers who used documentary films to inspire the masses towards Revolution and rejected the very idea of non-fiction films as appropriate to tell such rousing real life stories. Like Derain and Mayer, Vertov started out in the 1910's as a writer of both fiction and non-fiction, including film and photography. After the Russian Revolution he was the editor of a film magazine who became fascinated about the possibilities of documentaries as a medium for spreading revolutionary consciousness. In this he was thinking along the same lines as Lenin and Trotsky who had long seen film as a propaganda tool. Although it is often not not fully recognized in Europe and America who when looking at the first generation (pre WW1) of film tend to focus almost exclusively on America, France and Italy, Tsarist Russia was an important centre of film production with a rich and popular catalogue of films covering a number of genres. Lenin (who in his pre-revolutionary career had been an aspiring pianist and writer) and Trotsky (another aspiring writer) quickly spotted the role film could take in reaching the masses with a dramatically presented message that would have more emotional impact than written the traditional pamphlets, newspapers and speeches, especially given that many of those masses were functionally illiterate and the sheer number of languages spoken in Russia. The resulting films were called "Agit-Prop" for "Agitate-Propagandize", itself a take on the Polish/German revolutionary Rosa Luxembourg's "Agitate, Educate, Organize" slogan. Film must not provide propaganda, it must also inspire and rouse the masses to action by portrayal of the regular man playing a role in creating the new workers state. Paul Strand of "Manhatta" and Joris Ivens were also Marxists but while their later sound film work would present such ideas in more conventional documentaries their city films were almost entirely free of such themes. One could argue that perhaps Walter Ruttmann may have been content to leave a few hints and veiled political subtexts but Vertog was a revolutionary working within a system that still saw itself as promoting a revolution to liberate mankind from the chains of reactionary repression and that led to a very different approach. As a film critic Vertog was disdainful of fictional films including those of Sergei Eisenstien ("The Battleship Potemkin") who he dismissed as phony and manipulative, only documentaries could present the truth. Starting in 1922 Vertov started a series called "Kino-Pravda" ("Film-Truth") which made a series of two dozen newsreel type shorts that showed aspects of Russian post-revolutionary society as one on the move, building a new world. He focused for the most part on working people and farmers rather than promoting a leadership cult (unlike later Soviet and Nazi films) and even occasionally showed problems yet to be overcome including the poverty of the rural and urban poor albeit with the implication that such problems could and would be solved by hard work and the new leaders. A notable difference with the films of Ruttman, Sheeler and Ivens was that while they were focused on the form and function of machines, buildings, trains, boats etc, Vertov was more interested in the people or at least the society they represented. Vertov was also more willing to take the sort of flashy camera tricks used on occasion by Ruttman, Ivens and Derain and give them full rein for a more kinetic experience.

"MAN WITH A MOVIE CAMERA" (1929)

(soundtrack by Zoviet France)

Right away we see a difference from the previous films; while those had all started with POV shots of entering the city by boat or train, this time we open with a trick shot of the titular Cameraman surveying his subject. In the films of Ruttmann etc the cameraman had been anonymous here he is a visible character. Although Joris Ivens had opened "Die Brug" in a similar shot he was not visible for the rest of the film, here cameraman (and Vertov's brother) Mikhail Kaufman will be visible throughout, walking the streets, setting up shots and occasionally interacting with people. This removes the distance of Ruttmann's film with a more personal approach, as if the Cameraman is bringing the viewer on a tour and making them part of the experience compared to Ruttmann's cool, aloof study. Not only are we shown scenes of the Cameraman at work, we are also shown early scenes of the film being developed and edited (by Vertov's wife Yelizaveta Svilova) and later being shown in a theatre. This film acknowledges both it's subjects and audience and has an open intent the way the previous candid "fly-on-the-wall" films did not. While previous films were almost entirely done with seemingly candid cameras here we not only have the constant presence of the Cameraman with us, we also see subjects occasionally acknowledge the camera with one woman even shielding her face with a handbag. We are made clear we are part of a movie being made as opposed to being a passive observer and any Soviet audience would assume there must be a message for this which there is. While the film is a sort of propaganda, unlike most propaganda it actually draws attention to that fact which invites the viewer to be part of the experience rather than just a passive audience which in turn makes the film's message of empowerment and making a new society more personal.

While Ruttmann made a veiled reference to the circle of life by showing a bride entering a church juxtaposed with an elderly lady slowly making her way up the church followed by a horse drawn hearse going through the streets. Vertov has no need of subtlety; he shows couples lining up to register for their marriage (some seem uncomfortable with the camera) then switches back and forth between a (quite graphic) birth and a funeral procession. We see a fire brigade rushing to work and an injured man in obvious pain. Then we shift again to a woman in a beauty salon juxtaposed with working women who have decidedly unglamorous jobs although both are shown smiling at the camera. The work of mundane (but still happy) seamstress and weavers is intercut with shots of the film editor we have already met at work signaling that both jobs are in fact creative and valued. While Vertov appears to keep to Ruttmann's framing device of following a day-in-the-life of the city his day is rather more free than even the frenetic but still structured Weimar Berlin.

Vertov and Kaufman make use of many of the same trick shots and effects Ruttmann had used and so there are split screens, slo-mo, fast motion, reverse projections, freeze frames and multiple shots of machines and objects appearing to come to life, but there are far more of these type of shots than Ruttmann had used. Vertov also has an extended scene of athletes at a track and swim meet. Ruttmann had also shown various athletes at races but while Ruttmann (or rather Freund) shot these scenes quickly and from afar, Vertov has them shot in closer and in slow motion which actually makes these scenes more kinetic than the real-time but distant shots in "Berlin". All of this makes this film seem far more fast moving than the rather passive previous films. In place of the glamorous nightlife of Berlin or Paris the after work pleasures of the proletariat are shown as more wholesome and healthy with plenty of sports and a city fair with rides and a magic show for happy kids and parents, by contrast the children in "Berlin" looked rather more scruffy and played alone. We end up where we started, at a movie theatre where an appreciative audience watches the very film we have been watching being filmed. We have come full circle as increasingly fast paced and sped up shots of the city race ultimately resembling the much later film "Koyaanisqatsi". However while Vertov uses more tricks and effects tham Ruttmann his film is still far more humanist. His human characters are centered and celebrated while Ruttmanns are observed passively from a distance. Reviews comparing the two films took note of this and largely prefered Vertov's city to Ruttmann's as being more energetic, alive and hopeful while Ruttmann's Berlin was cold and impersonal. Even though Ruttmann's Berlin has more glamour in it's nightlife at the end it is undermined by the drab and utilitarian nature of most of the rest of the film, whereas Vertov's film shuns such bourgeois trappings as cabaret it's more proletarian pleasures seem more wholesome and fun, especially since everybody in his film seems so happy while people in Ruttmann's Berlin seem rushed and preoccupied. One notable difference in the films is that while Ruttmann's film was shot in and named after Berlin and previous films were clearly shot in specific cities such as Paris, New York and Rotterdam, Vertov's was not in fact shot in a specific city. The film was actually shot in the cities of Moscow, Odessa and Minsk and thus is not really about a specific city at all but instead shows the workers in Soviet cities writ large.

There is little overt propaganda with Vertov's film with only one passing shot of Lenin and that is of a portrait above a door. It's worth noting that while Stalin would later foster a personality cult Lenin disapproved of this and the ubiquitous statues and portraits of Lenin would come later. There is also a shot of a bust of Marx at a worker's club which Lenin would have approved of however. There is one sequence at the city fair with a woman at a target booth shooting at a figure wearing a hat with a swastika which shows foreshadowing of the future entirely missing from "Berlin" even though the Nazis would not even take power for another four years and war itself was a decade away. While the political message of this film is not heavy handed does not mean that this film is not still propaganda however. Vertov was a Marxist and set out to make a film celebrating the fruits of the Revolution. The workers are meant to be glorified as they make a new Marxist society instead of being mere products and consumers of a capitalist one. Workers are always shown as being both happy and productive, with many close ups of smiling faces, while Ruttmann's focus is on the machines and the workers are incidental. Even Vertov's consumers, particularly the women and the beauty salon, are shown intercut with other women happily at work but not contrasted with them. Like Ruttmann, Vertov has shots and montages of machines at work and they share a fondness for store window dummies. But in Ruttmann's film, either by design or not, Ruttmann's dummies often seem more animated and lifelike than his people (he certainly is more fond of showing their faces) and that is not true of Vertov. Ruttmann's film is not entirely without a political and social subtext as he does contrast scenes of wealth with extreme poverty but he does so with his usual clinical detachment. Even the scene of the anguished woman drowning herself is done in a manner which is at first striking but rushed and then quickly forgotten as the city hurtles on. We learn absolutely nothing about her nor does anybody seem to particularly care. Since this is the one scene in Ruttmann's film that was obviously fully staged he must have had some intention here but we don't know what. Was she a victim of the poverty we get a glance at? Or was she just overwhelmed by life in the fast paced, impersonal city? Or was it a more personal tragedy? We get no clues.

In the debate over the two films Vertov would sniffly dismiss the idea that he had been influenced in anyway by Ruttmann's work and Carl Mayer himself would criticize Ruttmann for his "surface approach" on the other hand Sergei Eisenstien (whose own films Vertov had criticized as phony) would dismiss it as "pointless camera hooliganism". However that comparison is not entirely fair since the intentions of the two were completely different; Vertov was a polemicist who set out to make a film with an overt message while Ruttmann and Freund (if not Mayer) were artists and craftsmen working on a visual project, not a political one. Freund and Ruttmann's camera was almost entirely candid and it's subjects unaware so Freund had to shoot and use scenes as they presented themselves and then Ruttmann would assemble them into some sort of vague narrative, while most of Vertov's scenes were setup or arranged beforehand with the involvement of his subjects. This is why Vertov can arrange all those shots of happy workers, they did not happen spontaneously. Vertov had already made clear his intent as a polemicist in his various essays and his previous "Kino-Pravda" series of shorts. Ruttmann by contrast had shown in his previous work that he was a master craftsman with no obvious message and this would continue in most of his subsequent work, even that which was clearly done for propaganda as we shall see.

The question of preferring Vertov to Ruttmann is somewhat complicated by Ruttmann's later work for the Nazis. In 1933 he tried his hand at a proper feature film with "Acciaio" (AKA "Steel") a gritty melodrama shot in Italy with an Italian cast, about a lover's triangle among the working class set in a steel mill. Once the Nazis seized power in 1933-34 many of his fellow filmmakers fled the country. This included the likes of Fritz Lang, Hans Richter, Marlane Dietrich, Brigite Helm, Asta Neilsen and Conrad Veidt as well as Carl Mayer and Karl Freund. Ruttmann however did not. Instead he stayed and found work with Leni Reifenstall as an assistant on her infamous Nazi propaganda films as well as working on newsreels for Joseph Goebbels Ministry and making a number of propaganda films most of which are not currently available with two exceptions. "Deutsche Panzer" (1940) is a short film about the making of the Tiger Tank and as such it is somewhat predictably focused on the mechanics of the process with plenty of gleaming metal and could just as easily be a film about the building of a British or American tank. There is nothing particularly fascist about this film. In fact the Allies did produce very similar (if less stylish) films about their own war machines and would continue to do so in the Cold War and into the Space Race. The one difference between this film and comparative films made by the Allied Powers is in an early scene which shows school kids learning engineering so they can become tank builders for the future. The incorporation of children as cogs in the unified Nazi state is a common theme in authoritarian states and would not have turned up in a similar films about building the Spifire or B52.

"DEUTSCHE PANZER"(1940);

Ruttmann's political views are contradictory, he was a pacifist who had spent time in the USSR advising Soviet filmmakers but unlike many other filmmakers he did not flee Germany when the Nazis took power. His decision to stay in Germany while many of his colleagues fled could be explained by any number of reasons; he had a successful career and did not want to start over again, perhaps like the actor Emil Jannings he spoke no other languages fluently. Like Hans Richter (who did flee) he had roots in the Dada art scene the Nazis would ban but unlike other Dadists he had already moved beyond that world into the mainstream where he had made films for advertisements and could continue to find work. Unlike Peter Lorre, Conrad Veidt and Brigitte Helm he did not have a Jewish roots or a Jewish spouse nor had he been involved with leftist politics so he was in no particular danger himself as long as he toed the line. What few hints there are in "Berlin" and his previous Dada Op Art shorts as well as the Dada milieu show him as having vaguely liberal beliefs; He does show poverty (but does not draw any larger conclusions), he is comfortable with the sort of people the Nazis would vilify such as blacks and Jews, avante garde artists and writers who he does not vilify or mock. His entire filmography shows him as a master craftsman meticulously exploring the latest in film (and later sound) techniques and like Charles Sheeler a fascination with the form and function of structures and machines with comparatively little interest in people who are mere supporting players. It can be been pointed out however that an obsession with form and function to the exclusion of humanity is a common theme in Fascist art, allowing the artist to both glorify the power of the regime's power at the expense of the people who are mere cogs, easily replaceable, and distance himself and his audience to those who are not useful to such a system. In such a system a talented craftsman with no strong views or personal stake can make a comfortable living as long as he keeps his head down and does his job. That is in fact the basic defense offered by Leni Reifenstall herself to defend her work for the Nazis. In her case these excuses are now seen as being at least somewhat disingenuous and her links to the Nazis were more explicit than she let on. Ruttmann's case is less known as he did not survive the war and apparently left no record on his thoughts so we have to judge him on his work. As stated, almost all of his work that survives is not inherently objectable with the notable exception of one film. During World War 2 Ruttmann was wounded while shooting footage for another propaganda film and died of complications of his injuries in 1941.

"BLUT UND BODEN" (1933)

This film is the worst sort of Fascist propaganda, not only for it's message, which is vile and dishonest, but even setting that aside, to the extent that's possible, it's also bad filmmaking. This is strident, hectoring, lacking in any subtly and deprives the audience of the power to think or feel for themselves. In the film a German farm family have their farm foreclosed on, are forced to move to the city which is shown as crowded and alien and eventually return to farming in the German East. These parts of the film are done as melodrama with actors. The rest of the short film uses both animation and montage to present the case that the German farmer is suffering because alleged financial interests and banks flood the market with foreign produce, refuse to lend money for the manufacture of farming equipment and foreclose on people's farms. This film also advances another Fascist trope which advocated depopulating the cities, which they considered decadent and full of undesirable Jews, gays, intellectuals and leftists in favour of "returning to the land" and homesteading to revive the Ayran Herrenvolk's mystical relationship with "Blood And Soil" and colonizing the lebensraum the Nazis were expecting to open up in the east. This film is completely at odds with everything else Ruttmann ever did and it is certain that he did not write it. Instead it resembles the propaganda put out by Joseph Goebles both in message (of course) but also in it's style which is both strident and pedantic. The final scenes of happy Hitler Youth and Labour Front marching through the countryside with Nazi flags waving and dramatic music in the background could have been lifted from any propaganda film from Germany, Italy or the USSR. It leaves no room for subtlety although unlike other films from Goebbles propaganda mill it does not explicitly attack the Jews. Ruttmann's films have been criticized for being cold and remote but he had a lyrical sense and whatever message he had was implied through visual cues, not lectured through a droning narrator or rote acting. It would seem that Ruttmann's role here was to deliver some competent visuals for the city sequences for which he recycles some footage from "Berlin" which is probably why he was hired in the first place. This is ironic since Ruttmann's very existence is the opposite of the message of this film. "Blut und Boden" glorifies farm life and demonizes the city. Ruttmann was a product of the city and Avant Garde art scene and yet he is willing to trash it for the new masters. That this was a project done under orders and over which he had little or no input can be seen in how little this looks and feels from his other films which were innovative and imaginative, this one is dull and perfunctory, clearly he was not inspired by the assignment. Unlike Leni Riefenstall who did take obvious inspiration and energy from the Nazis for her films, Ruttmann seems bored, at least with this film, in "Deutsch Panzer" he is back in his element, with loving shots of gleaming machines. Whether Ruttmann was an actual Nazi or simply a craftsman who had made his peace with a totalitarian regime and was simply doing an asignment he didn't care enough to put much thought into this vile film is a blot on Ruttmann's legacy and makes more complicated the debate over Ruttmann's vs Vertovs's films.

However if it is fair to prefer Vertov's exuberance and optimism to Ruttmann's cool dispassion and to take into account the latter's work for the Nazis it must also be fair to look at Vertov's work and the regime he worked for. Only the last few films Ruttmann made were propaganda films, any other political motivations in his other work can only be inferred through hints and impressions and they are contradictory, Ruttmann is the product of a democracy, however strained and fragile, Vertov on the other hand was a revolutionary polemicist from the start and his film were expressly meant to promote the revolution. Comparing their early work is instructive. Ruttmann came out of the same Dada art scene as Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling (who I've written about here) and all his work prior to "Berlin" were experimental Op Art or animated shorts with no human subjects or obvious political subtext.

"LICHTSPIEL I-IV" (1921-25);

Vertrov on the other hand was making newsreels designed to promote the Revolution and specifically the Bolshevik faction of Lenin. His "Kino-Pravda" series of 23 shorts starting in 1922 were named after the Russian words for "Film-Truth" as well as not coincidentally using the name of the Bolshevik's official paper "Pravda" which had been published since 1911. These shorts used mostly authentic footage along with some staged scenes to tell the story of the successful revolution, a hopeful new society rebuilding, threats from within being crushed (in the form of the rival Socialist Revolutionary Party who are shown on trial), Lenin as a dynamic leader and later after his death as a beloved fallen father figure. One of the later episodes of the series, shot after Lenin's death serves as a compilation of "Kino-Pravda" episodes.

"KINO-PRAVDA" EPISODE 21 (1924);

These newsreels are the polar opposite of Ruttmann's Op Art and animated shorts; where Ruttmann's shorts are artistic experiments Vertov's are fairly conventional in form aside from being faster paced and with quicker edits. Where Ruttmann's shorts have no real political or social content, or for that matter any content at all aside from the animated shorts he did as ads, Vertov's shorts are in effect all promotional ads for the Bolshevik regime. Ruttmann was an artist experimenting with shapes and forms in a new medium only later, after "Berlin", was he hired to make a few propaganda films. Vertov was a polemicist experimenting with a new medium and only by "Man With A Movie Camera'' could he be said to be really exploring the possibilities of film in a more artistic way. At the time their two classic City Films were made their backgrounds and intentions were completely different. Critics have taken some issue with "Berlin" as lacking the vibrancy of "Man With A Movie Camera" and blamed the distinction on the fragile Weimar society as well as Ruttmann's cool indifference to the social and political nature of that society on the verge of collapse. But all this is of course hindsight, Ruttmann can hardly be blamed for not forseeing the Nazi takeover five years later and at any rate that was not the purpose of the assignment he and Freund were given. They were supposed to tell the story of a day in the life of the great city and that is what they did. They could have possibly shown some footage of Nazi Brownshirts marching or brawling in the streets but their mere presence would have been jarring and changed the focus of the film making it clearly political in a way it was not intended to be. As stated it must also be remembered that Berlin was not a paticularly friendly city for the Nazi Party anyway (something Hitler always resented, after he became dictator he made plans to build an entirely new capital to be called Germania, Berlin was to be largely depopulated) and it's possible that while Freund was shooting he just didn't come across any Brownshirts. Critics at time and since have prefered Vertov's scenes of energetic and happy workers to Ruttmann distantly observed impersonal subjects rushing about without purpose but in hindsight we can now spot these as common tropes of authoritarian propaganda where the people are united with the wise and strong leader and the party in a sense of united purpose. Ruttmann's work may be cool and remote but "Berlin" is not authoritarian, Vertov's films are. One of his later films "Enthusiam" (1931) is classic Soviet propaganda in the style that would essetially remain the same for the duration of the Soviet Union's existance and would be copied by regimes from China and Vietnam to Iran as well as Facsist Italy and Nazi Geramny, albeit done with his usual sense of energy and by now kinetic camera work and editing.

"ENTHUSIASM" (1931)

If we are going to take into account Ruttmann's later work for the Nazis in judging his work then we must also do the same with Vertov. Just as hindsight places "Berlin" in the context of a society on the brink of collapse, praise for the vibrant and energetic society and happy workers Vertov's films show can not be seen without the hindsight that we are seeing a society heading into a complete totalitarian police state, something Vertov is an active cheerleader for. To be fair to Vertov these films were made from 1922 to 1925 or 26 with "Man With A Movie Camera" being made in 1929 and at that time the full repression of Stalin had not yet happened. In the 1920's it was still somewhat possible to believe that the worst excesses of the Revolution were over. 1922 had seen eight years of war, revolution, civil war, terror and famine but by 1929 it was just possible to believe that the future was indeed bright; there was peace, the economy had picked up and Soviet society was visibly on the move. That was indeed the sincere position most (but certainly not all) Marxists took at the time both in the Soviet Union and abroad. Lenin had died in 1924 and Stalin had taken over but he had done so peacefully and his power was not yet absolute. The horrors of Stalinism, the purges and show trials, more famines, ethnic cleansing of Tartars and other groups, mass arrests and terror. Vertov's films do actually show a few muted criticisms of the Soviet government with scenes of extreme poverty and famine in some of the "Kino-Pravda" shorts and a few fleeting views of what seem to be homeless men in "Man With A Movie" camera albeit this is done within that larger context of the theme that the dynamic new Soviet government and it's bold leader Lenin are fixing the problems. Lenin was actually not opposed to all criticism and debate as long as it was deemed "constructive" and "positive" and would not have minded this, but under Stalin any and such critiques, however veiled, would not be allowed. Vertov can be somewhat excused from predicting, much less showing any of the horrors of the regime but only somewhat, he was still an enthusiastic propagandist for a regime that even under Lenin was hardly free and had committed many crimes and atrocities which Vertov ignores and there is nothing to indicate that even privately he expressed any doubts. "Enthusiasm" shows he is still a cheerleader for the by now clearly Stalinist regime. Like Rutmann under the Nazis he would have had little choice in the matter whatever their private thoughts but if the dark shadow of the Nazi regime is in hindsight seen to hang over "Berlin" and if Ruttmann's later propaganda work is to be counted against him than Vertov must be held to the same standard. After this film Vertov and his brother had a falling out and did not work together again although Vertov would continue to make films for awhile until his flashy style fell afoul to the increasingly stodgy censors of the Stalinist era and he ended up as a low profile editor of newsreels dying in 1954 aged only 58, outliving Stalin by a year. His brother Mikhail dropped out of film and became a photographer, dying in 1980. Vertov's wife and editor Yelizaveta Svilova continued to work with Vertov but retired from film after his death to concentrate on assembling his various writings. She died in 1975.

DZIGA VERTOV

Update; I wrote a later article about Vertov's earlier newsreels which you can find here.

===================================================

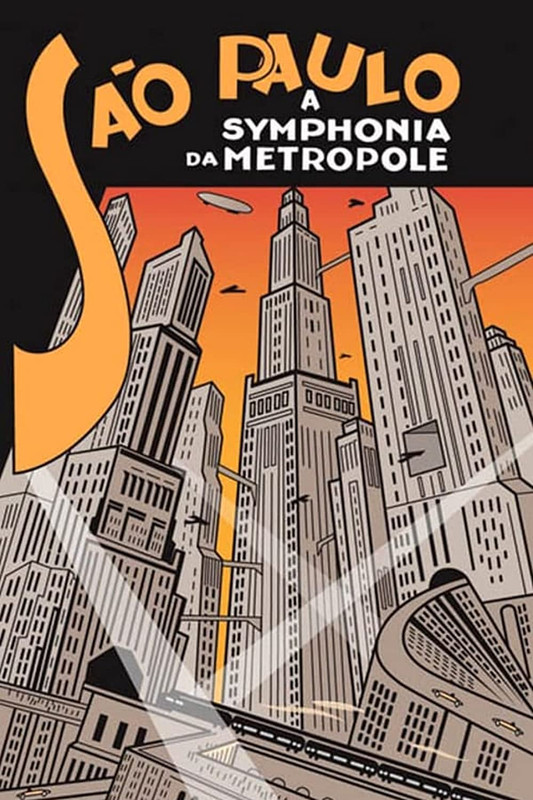

The genre of City Symphonies would end with the coming of sound, audiences would not be interested in long form documentaries without a narrator when they could now have dialogue and music. Also for the first few years of talkies the bulky new cameras and sound recording equipment were not capable of rushing around or being as covert or adventurous as Ruttmann, Vertov, Sheeler, Ivens and Derain had been. There would however be one last film in the genre which would take lessons from both Ruttman and Vertov. "São Paulo, Sinfonia da Metrópole" (dir. Adalberto Kemeny, 1929) was another full length city film this time away from the usual film hotbeds of Germany, France or America and instead to the new frontier of Latin America.

"SAO PAULO; SINFONIA DA METROPOLE" (1929);

As with "Berlin" we start in the morning with people going off to work. We see a milk bottling plant, then a milk delivery truck, street sweeper, kids going to school, a traffic cop, street venders and shoppers at a market. So far we are firmly in Ruttmann territory although director Alberto Kemeney lacks Ruttmann's confidence to allow the images to speak for themselves and instead uses a fair number of inter titles even when they are not needed. Do we really need to be told that kids are going to school and are later in class? He uses some montage effects and tricky camera angles taken from Ruttmann or Vertov, but is otherwise straightforward in his approach. As with "Berlin" we break for lunch although Kemeney mostly with the working men for this scene, however he does show wealthy neighbourhoods at other times. After lunch he switches gears a bit and becomes more of a travelogue as he points out the sights such as some government buildings and the flag being raised. At this point the focus shifts again from detached observer and instead becomes a promo for the New Modern Brazil. We see a montage including Sao Paulo with Paris, New York, London and Athens, clearly setting them as equals. We see telegraphs and newspapers connecting them and thus Brazil with the outside world. After an odd scene about harvesting snake venom we spend an extended sequence at a reformatory which is presented as a clean and modern institution where criminals are reformed. We are now no longer in Ruttmann territory of dry observation but Vertov's world of film as an advocate, namely of Brazil as a modern, up-to-date democracy forged in a successful liberation. We get an extended historical scene paying tribute to the liberation with cavalry troops charging back and forth (a similar scene that Vertov used in the "Kino-Pravda" newsreel), along with scenes of a church and baptism to make clear that unlike Vertov's Soviets, Brazil's founding was a national Liberation not a social revolution. Notably the independence troops who fought for independence are not the proletarian revolutionaries of the Russian Revolution but upper class cavalry officers. In fact one glaring omission from this film compared to Ruttmann's Berlin or the Paris films, or even Vertov's USSRis any suggestion of social strife at all. Even though Brazil was (and is) known for it's sprawling poverty stricken slums and ricketty favelas there is not a hint of that here. Like Vertov, Kemeny is a cheerleader and this film is meant to inspire national pride. When we get back to the city we are shown building sites but in the context of the film they represent progress as the intertitles brag about the number of new buildings going up. We get scenes of factories, warehouses and rail yards, all clean and efficient. The workers do not have the revolutionary zeal of Vertov's, or the determined pride of Ruttmann's in "Deutsche Panzer" in fact oddly we don't get any close-ups at all suggesting Kemmeny didn't learn all the lessons from them. He was clearly aware of the earlier Dada short films of Ruttmann, Hans Richter and Viking Eggeling though as we get a sequence of Op Art effects and a montage of whirring gears, clocks and metronomes to symbolize progress and technology. There follows a frankly incomprehensible sequence of more Op Art spirals, shots of various zoo animals spinning numbers and some trick photography that would not be out of place in a Dada film which seems to include some sort of message about charity but it's impossible to see what the point of it is. Following that we get some cryptic intertitles which when translated into English appear to celebrate the virtues of consumerism then showing some wealthy women window shopping while their chauffeurs play cards and wait for a scene that definitely would not be found in a Vertov film. We do get the by now standard sports footage which has some sprinters emerging out of a race official's bullhorn that Vertov would have approved of. A scene at a pool gives Kemeny the excuse to use some trick shots of swimmers going backwards up a water slide for no obvious reason. In another contrast with Vertov for the rest of the sports scenes instead of the shots of happy prolatarians playing together we have elitest spectator sports like rugby and horse racing which then leads to patriotic scenes of an army unit on parade saluting the flag which a salute that looks uncomfortably like the Nazi Sieg Heil. To be fair given the date the resemblance is a coincidence but it does display between the casual looking Red Army peasant soldiers of Vertov's film with the spit and polish authoritarian soldiers here. Followed by more charging cavalry, again these are not the rough and ready cossacks of Russia but aristocratic cuirassiers in shining helmets followed by an intertitle that reassures us that they are fighting for "Progress". Then we go back to the city for more traffic scenes and a fire brigade rushing off to a fire we don't actually see. The rest of the film ends with more street traffic scenes. While "Berlin" and to a slightly lesser extent "Man With A Movie Camera" went from morning to night and thus had had a beginning and end this film starts with the morning but then meanders and sort of sputters to an end with a tolling bell then a sudden shot of an imagined future city using a "Metropolis" type skyline of skyscrapers and a sky full of buzzing planes and zeppelins.

Although this starts out resembling Ruttmann's "Berlin" midway through it is clear Kemeny's influence is in fact Vertov. Like Vertov he is a propagandist with a message, namely that Brazil is a forward thinking (the word "Progress" is frequently used), modern society to be seen as equal to those in Europe or America. In fact while Sao Paulo does not look like Berlin, New York or Rotterdam exactly it doesn't look wildly different either. There is no indication of the poverty of the favelas outside of town or the more primitive rural and jungle areas. We see the same cars, trams and trains. The same factories and machines and, allowing for differences in architectural styles, those same buildings. Although some of the working people dress in rougher clothes than their German, Dutch or American counterparts, the middle class women in their cloche hats and bobbed hair could just as easily be shopping in New York or Berlin. Unlike authoritarian propaganda no reference is made to any specific modern leaders and this film is not to glorify some strongman but instead the nation as a whole. Unlike Vertov, Kemeny's message is muddled however and at times the film loses focus and meanders. He also lacks the strong editing sense of Vertov, Ruttmann or Ivens as some scenes drag on, notably the reformatory scene. Like Ruttmann and Vertov, although to a lesser extent the message of the film is now weakened by the flow of history as we know that the optimistic view of Brazil's future would actually pan out. Within a few years of this film Brazil would be rocked by a series of coups, revolutions, civil wars, dictatorships and more coups that would last until today. The poverty that this film studiously avoids would become endemic and wealth inequality ingrained as the business, landowners and officer class, which this film celebrates, would line their pockets. For his part Adalberto Kemeny would direct no more films although he would be a cinematographer on a few more. He died in 1969 largely unknown outside Brazil.

==================================================================

The Berlin and Moscow films, whatever their artistic motives, were feature length films intended for a general audience. By the mid twenties there was a small but reasonably profitable network of arthouse cinemas that showed non-commercial art films from the likes of Dada filmmakers Hans Richter, Walter Ruttman, Man Ray, documentaries, City Symphonies and various other low budget, usually short form, films. There were small theatres showing such fare in a number of large cities with a Bohemian art scene in Europe and America. A surprising number of these films have survived in spite of never having a general release, notice from the mainstream media or backing of a major studio. In fact that last point may be why they did survive, major studios actively melted down or lost films through careless storage thinking them of no lasting value but many art films were squirreled away and made their way to libraries. The era of the City Symphonies would end as it started with a short art film shot in New York when silent films were already being phased out for the new sound era.

"SKYSCRAPER SYMPHONY" (1929);

"Skyscraper Symphony" was directed by Robert Florey a French director who had gotten his start working as assistant director for Louis Feuillade ("Les Vampires" and "Judex") before moving to the new film capital of Hollywood in 1921 where he worked again as an assistant director, publicist and newsreel director while making a few short art films including the odd "Life Of 9414 A Hollywood Extra" (1928) before making his entry into the City Symphony genre.

With this film we have ended up where we began. "Skyscraper Symphony" is very similar to Charles Sheeler's "Manhatta", a short film study of the skyscrapers of New York done in an even more self-consciously artsy style. As with Sheeler's film the focus is entirely on the buildings with almost no humans to be seen at all until the end where again like Sheeler he shows some construction work. In fact the film is so devoid of signs of human life New York actually looks like a ghost town or a post apocalypse. An uncomfortable effect enhanced by having some swaying camera shots, passing dark clouds as well as some shots done from below giving the illusion that some of the buildings appear to have no windows as if abandoned. This film is so similar to Sheeler's both in approach and structure Florey must have seen the earlier film but while Sheeler's New York may be cool and distant Florey's is down-right cold and forbidding. The ending seems truncated and it's possible the ending has been lost although it's doubtful very much is missing.

Florey would go on to a long and successful career making dozens of films including such mainstream fare as "The Cocoanuts" (1929), with the Marx Bros, "Murders in the Rue Morgue" (1932), with Bela Lugosi, "Meet Boston Blackie" (1941), "Tarzan And The Mermaids" (1948) as well as doing assistant work on "Frankenstien" (1931) and Chaplin's "Monsieur Verdoux" (1947). Still later he would make the transition to the new medium of television working on classic shows like "Twilight Zone" and "The Outer Limits" dying in 1979. He did not get to see this obscure film be rediscovered however as it was considered lost until the 1990's when a copy turned up in film library in Moscow.

======================================================

In classical music there is a superstition that the ninth symphony is cursed with a number of composers dying after composing their ninth. Most of the City Symphony filmmakers had similar bad luck after making their symphonies with only Ivens and Florey having a long life and career. Although the genre faded away with the coming of sound aside from the 1982 film "Koyaanisqatsi" being the obvious successor but "Man With A Movie Camera" and "Berlin; Symphony Of A Great City" are considered among the most important documentaries of all time with the debate over which was better still unresolved. Ultimately Vertov's film is more energetic and lively while Ruttmann's film is less manipulative and more honest. All these films are a unique and invaluable look into urban life in the first quarter of the twentieth century.

No comments:

Post a Comment