Over the past decade or so there has been an increased interest in the beginnings of Black Cinema in America with note being taken by the works of Oscar Micheau in particular (who I had previously written about here). However even as Micheaux's serious, somber and ambitious films were aiming to "uplift the race" there were others who sought to simply provide entertainment producing lowbrow slapstick and low budget adventure films to match those in the larger world of white cinema and Vaudeville.

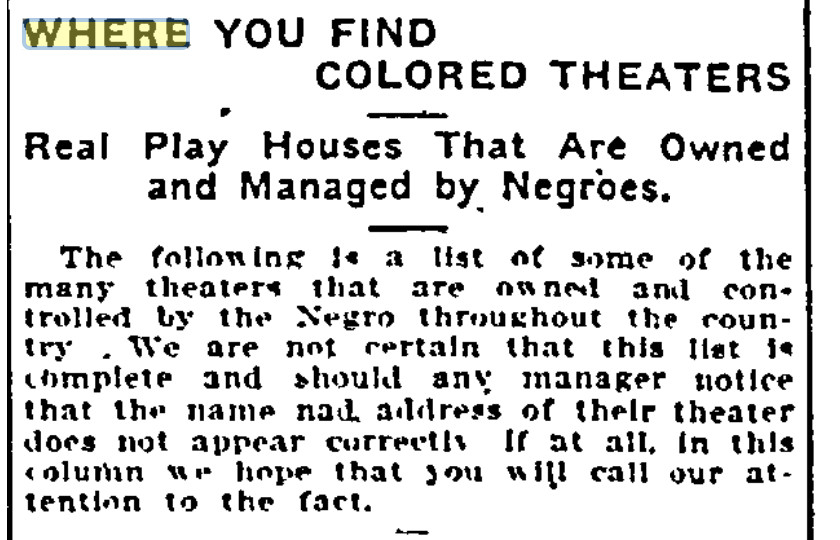

Vaudeville had in fact taken some of its tropes and traditions from the earlier genre of Minstrel Shows which had swept the country in the mid-nineteenth century and provided the first example of mass entertainment in America. The history of Minstrelsy is too long and convoluted to detail here but it began as an authentically black form of comedy, music and dance which by the mid-century had developed a star system of touring acts both black and white. By about the 1880's the large and rather formalized travelling Minstrel shows had in effect been broken down into smaller parts that would make their way into smaller and cheaper white owned Medicine Shows in rural areas and Vaudeville in the cities. A network of Vaudeville theatre chains would stretch across the US and Canada much as later movie theatre chains would do and while these theatres would provide opportunities for black entertainers they would also have to put up with the insults and indignities of the Jim Crow era and by the 1890's a parallel network of black owned theatres had sprung up across the country.

Inevitably once movie theatres largely replaced Vaudeville this model would eventually be recreated with chains of black owned movie houses. These theatres, usually small, existed in black neighbourhoods in big cities like New York and Chicago to smaller towns into the South along with travelling tent shows in more rural areas that could set up a screen and projector. Besides these black owned enterprises in some cities white owned theatres in black neighbourhoods would set aside a day of the week to program movies with black stars or all-black casts for what were called Midnight Rambles. Naturally the existence of such networks required a regular stream of such movies which would be filled by a variety of movies of various genres ranging from the serious minded social melodramas of Oscar Micheaux to more lowbrow fare including musicals (including by Louis Jordan who I wrote about here), comedies, film noirs, romances, even westerns (including those of Herb Jeffries (which I also wrote about here) and at least one monster movie in "Son Of Ingagi" (written about here). Most if not all of these films were made quickly on a low budget, were largely unknown to the larger white audiences and have until recently been largely ignored by film histories with many being presumed lost.

Some of these all-black movies were indeed produced and directed by black filmmakers the first of which was the Lincoln Motion Picture Company which ran from 1916 to 1923 making only five films from which remains only one feature and fragments of a second. Other films were actually produced by the same white owned Poverty Row studios who spotted an opportunity to churned out low-budget westerns and comedies albeit under different studio names. One of the first and most controversial of these studios was Ebony Films which operated of of Chicago in the 1910's. While the Lincoln Company's films were of a similar serious and ambitious nature as those of Micheaux, those of Ebony Films were another matter.

Ebony Films was in fact a white owned company which started out as Historical Features Films based in Chicago in around 1915. The name suggests that either they had ambitions to be making feature length epics or more likely that they wanted to create the illusion that they were and they do seem to have made some educational films. In the event the bulk of their films (most which do not survive) appear to be limited to comedies and a few rumored westerns. Given that they shot their films in Chicago one can assume their "westerns" were shoddy low budget affairs although in the 1910's when most films,including westerns, were still shot in New York and New Jersey (including "The Great Train Robbery" and the many shorts of Bronco Billy) this was not unusual. The studio's bread and butter however were its one reel comedies which by all accounts were of the lowest common denominator type of slapstick and full of "ethnic" humour which they openly marketed as such. By "ethnic" we of course mean "racist" with crude and insulting stereotypical tropes ridiculing various groups including Blacks, Asians, Jews, Mexicans, Irish, Italians and Native People among others long being popular fare in film and Vaudeville. However by the 1910's some of these tropes were becoming less fashionable with members of these groups begining to make their displeasure known. The 1915 release of DW Griffith's uber-race baiting "Birth Of A Nation" led to such a backlash from the Black Press and a organized campaign, probably the first of it's kind, to address not only protest the treatment of and portrayal of Blacks in show business but more importantly the creation of an alternative that would be owned and staffed by Black filmmakers and directed at Black audiences and t's not a coincidence that both Oscar Micheaux and Lincoln Motion Pictures began the following year.

"TWO KNIGHTS OF VAUDEVILLE" (1915);

The plot of this film, such as it is, is simple even by the standards of the slapstick genre. Two guys stumble onto tickets to a vaudeville show which have been dropped by a wealthy white man and they invite a lady friend to join them. At the show after a couple of (white) acrobatic and juggling acts the two men become so disruptive they are kicked out. They then decide it will be easy to put on their own show so they set up a theatre (in what appears to be an empty warehouse) and put on a show for an all black paying audience. However they are so inept that the audience heckles and pelts them with trash ultimately rioting and destroying the theatre.

This is slapstick film with performances of the two main characters (played by the obscure Jimmy Marshall and Frank Montgomery) being clownish buffoons behaving as naughty and rambunctious children, unsophisticated and dim with the ill-fitting clothes they wear being either oversized or too small. Defenders of the film may point out that such broad clownish characters were common in slapstick films of the 1910's including those of Mack Sennett, Charlie Chaplin, Fatty Arbuckle, Ben Turpin and Larry Semon and this is true. In fact some of these white characters are actually more clownish than those in this film. However these white characters are presented as exaggerated trickster characters living among the otherwise normal world of straight society and reacting to it in over-the-top ways. In this film the other Black characters (represented by the audience who riot at the end) are also childish and immature whereas the white characters are either authority figures (represented by the wealthy man, a theatre usher and a cop) or the vaudeville performers who may be slightly clownish but are clearly doing so in the context of performing on stage. The white theatre itself is also shown as an imposing building with columns and box seats compared to the warehouse the Black show is held at with plank benches and improvised curtain. The Black characters are in fact following the traditional tropes of the Black Face minstrel shows, with Blacks as clownish, childish, silly, unsophisticated and prone to violence. The one exception is the role of the Lady Friend of the two main characters. She dresses smartly and fashionably, attempts to restrain the others, does not get thrown out of the vaudeville theatre and in effect acts as both the straight man and mother figure. It may or may not be a coincidence that she is also notably lighter skinned than the other characters. The Black audience at the second show is also dressed respectably enough although they are quickly unruly.

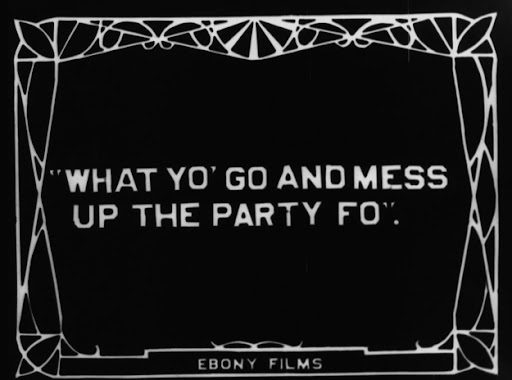

However what really gives the film's attitude towards Blacks which any Black viewer was bound to notice is the use of exaggerated and outdated Minstrel show speech for the characters who say things like; "What yo' go and mess up the party fo" and "Jest all time messin' up something. Nevah again". It's not just the two main clownish characters who talk this way as the signs put up announcing their performance are even worse with signs saying; "Vodevil 5 Sense", "Too famuz akters prezented on a big stage. Hear to day" and the performers billed as "Akrobats". Some of the letters are also transposed backwards as if written by a child. The obvious inference being that they are semi-literate and the all-black audience seems to accept this. The real life Black film audiences would not.

By the 1910's some of the use of racial and ethnic tropes were becoming less fashionable with members of these groups organizing to protest such treatment and even some white middle-class audiences becoming uncomfortable with such overtly demeaning subject matter. The 1915 release of DW Griffith's pro-KKK "Birth Of A Nation" led to such a backlash from the Black Press and a organized campaign, probably the first of its kind, to not only protest the treatment of and portrayal of Blacks in show business but more importantly call for the creation of an alternative that would be owned and staffed by Black filmmakers and directed at Black audiences and it's not a coincidence that both Oscar Micheaux and Lincoln Motion Pictures began the following year.

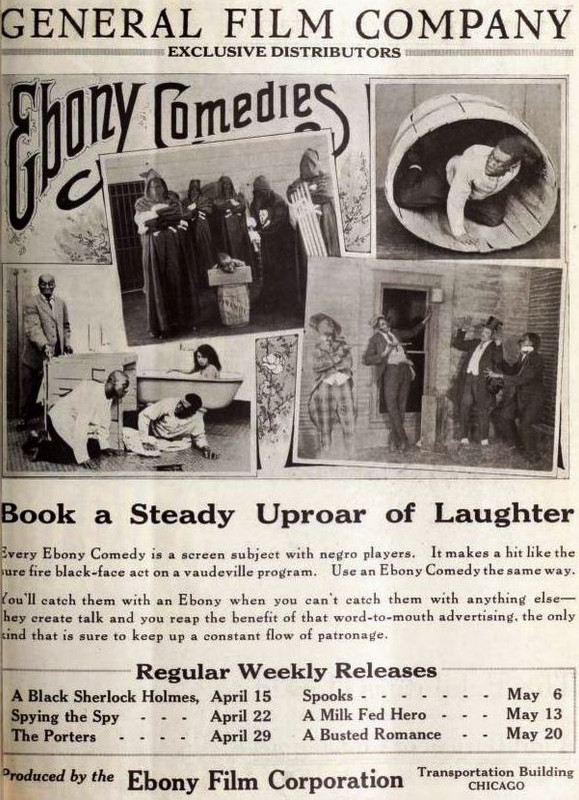

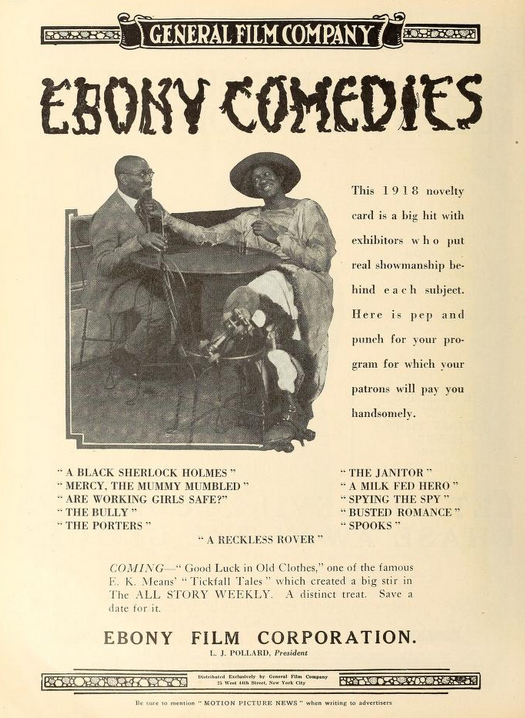

Meanwhile the white owners of Historical Films were facing a dilemma; their comedies were fairly successful enough with white audiences but were condemned in the Black Press as demeaning in ways they were no longer prepared to meekly accept. Faced with the choice of continuing to make their lowbrow films which while fairly profitable were embarrassing and had limited appeal or they could make some attempt to clean up their act. Somewhat surprisingly they not only opted for the latter option but they went all in on a complete makeover to appeal to Black audiences. Starting in 1915 they changed the name to Ebony Studios and hired an all (or at least mostly) Black creative staff and all-black theatre troupe and tried to appeal to both black and white audiences. For the next two years Ebony Films would make two dozen films, a respectable number, most of which appear to be comedy shorts, some of which parody white films including "Birth Of A Nation", westerns, adventure and spy films (including a Sherlock Holmes parody) and even monster movies. Until recently the output and quality of these films was mostly a mystery and none appeared to survive aside from some promotional material but over the past decade a collection of several of them have surfaced and can now be seen albeit in somewhat distressed or incomplete condition.

LUTHER POLLARD

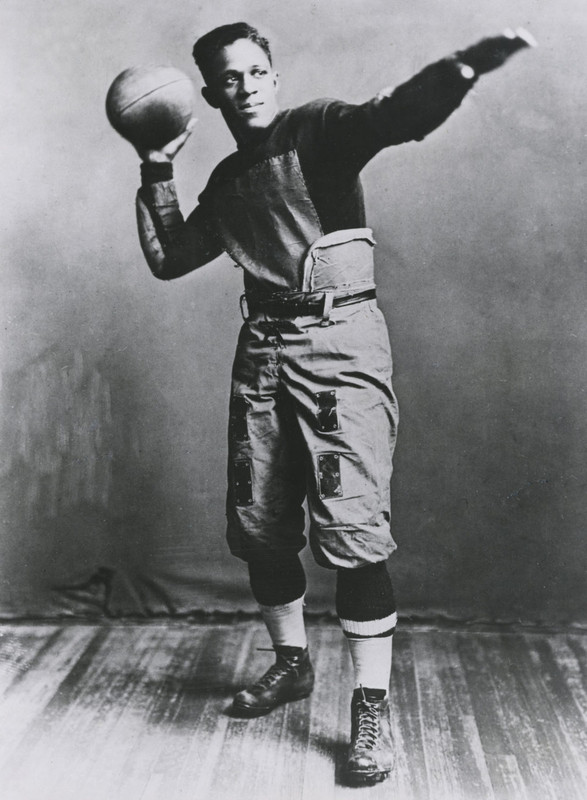

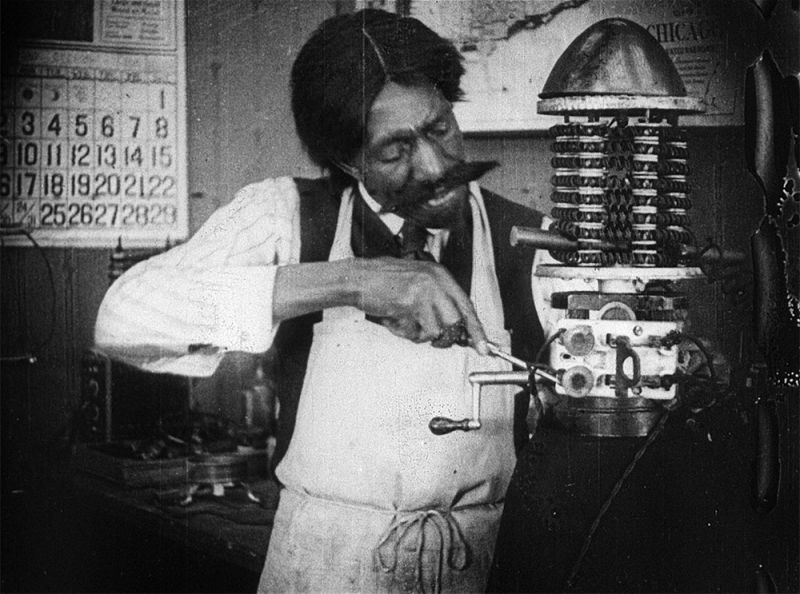

While the owners of Ebony Films may have been of limited talents the black directors and actors they hired were not. Chief amongst these were the Pollard Brothers, Luther and Fritz. Chicago native Luther, a writer and sometime director and was appointed President and General Manager and set to work bringing in his younger brother Fredrick Douglas (AKA Fritz) Pollard a charismatic figure who like the later Paul Robeson was an actor, writer and star football player who would also serve as a talent scout and casting director. It was presumably Fritz who hired George Lewis, an actor and director who already had his own theatre troupe in the George Lewis Players who would make up much of Ebony Pictures regulars in all of their subsequent films.

FRITZ POLLARD

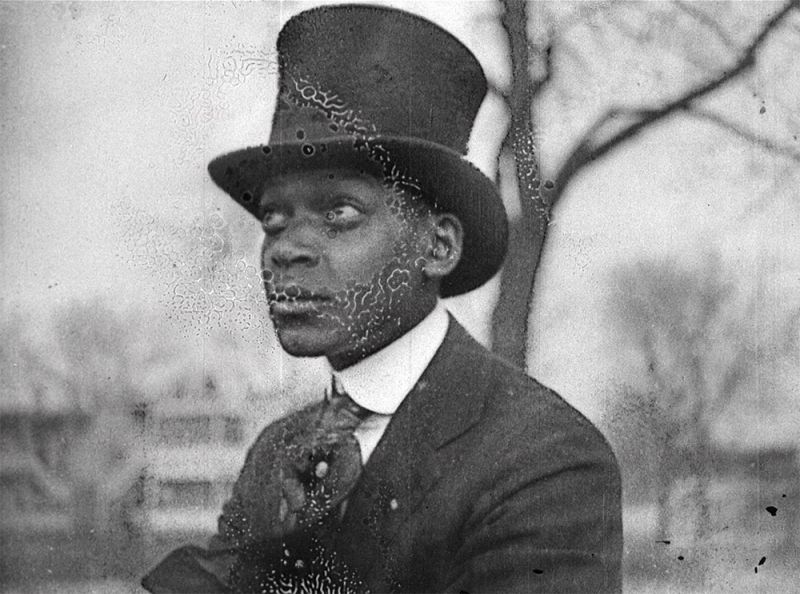

Among the players were leading man Sam Robinson, Rudolph Tatum, a sidekick, Sam Jacks, a tall straight man foil and pretty young leading lady Evon Junior (also billed as Yvonne). George Lewis himself would appear in supporting roles usually as a dignified authority figure foil as would the Pollard Brothers on occasion. Given that the troupe was named after Lewis it's likely Lewis played some sort of role behind the camera as well. He also appears older than Robinson, Tatum or Junior. From 1917 the cast of all of Ebony Pictures films seem to have come from the George Lewis Players. One notable difference in the later Ebony films of the era under the direction of the Pollard Brothers and George Lewis (at least those that survive and what can be gleaned from the others) from the earlier films is that not only are the casts are entirely or mostly black but they would exist in a world where Blacks would not simply be Minstrel Show stereotypes but also respectable middle-class figures. The clownish characters would remain as these were accepted slapstick tropes but they would exist in a larger world of respectable Black bourgeois society that would include Black professors, lawyers, doctors and businessmen as well as policemen and few white characters would be shown at all and if so only incidentally if needed by the story.

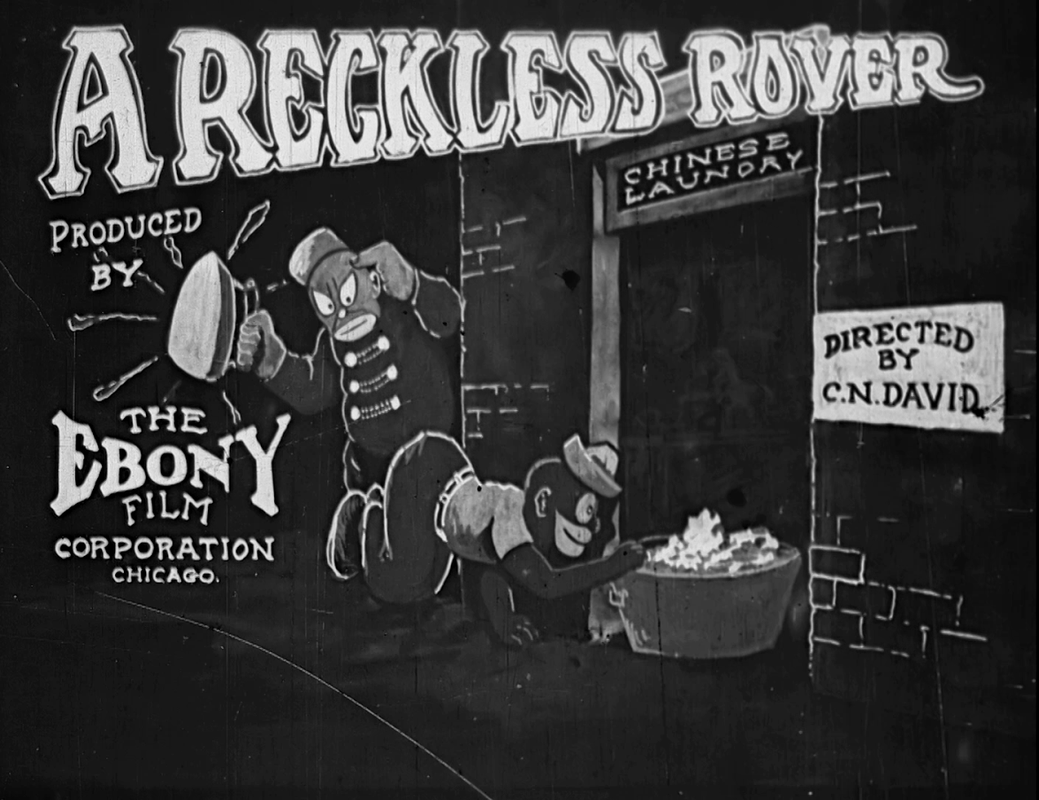

"THE RECKLESS ROVER" (1918)

Sam Robinson is a layabout named Rastus who is behind on his rent. His landlady gets a cop to throw him out of his room and after a chase he takes shelter in a Chinese laundry where the owner gives him a job. However due to Sam's incompetence and irresponsibility he soon causes chaos. Rummaging around the shop he stumbles on to an opium pipe and proceeds to get stoned. His over enthusiastic flirting with a young woman (Evon Junior) leads her to call for a policeman who of course turns out to be the one who chased Sam earlier and he again has to flee. Finis.

Here we see what would become the basic standard for Ebony films; broad slapstick humour and energy with Robinson playing a roguish bumbling oaf who gets himself in trouble. His character can be seen as perpetuating some racial stereotypes from Minstrelsy but is mostly within the bounds of a Mack Sennett slapstick film of the era. However the intertitle cards do use images obviously taken from the most racist Minstrelsy tropes as is the character name Rastus and it's not hard to see why Black audiences were outraged even if the cast is all Black. Besides Minstrelsy the film also includes a stereotypical Chinese coolie (complete with opium pipe). Trivia note; As in an early example of an Easter Egg as Rastus runs away we can see a poster for the DW Grifith movie "Hearts Of The World", but at least it's not "Birth Of A Nation". If Ebony was hoping to broaden their appeal this film can hardly be considered a good omen.

"THE COMEBACK OF BARNACLE BILL" (1918);

This is a rural based comedy in which Sam Robinson plays a bumbling farm hand with a crush on farm girl Evon Junior who is the daughter of owner Sam Jacks. After Junior rejects him Sam decides to go off into the woods and shoot himself but instead stumbles on to a couple of thieves who are in the process of hiding some ill-gotten money. He accidentally fires his gun and scares them off, discovers the money and takes it back to the farm where he hides it. Meanwhile Junior has a young suitor, Hector, visiting from the city and the family head off to pick him up at the train station in a horse buggy during which Sam tries to foil his bumbling. Arriving at the farm Hector tries to impress with his golf skill which more of Sam's bumbling interferes with causing more chaos. Meanwhile a lawyer (George Lewis) arrives to foreclose on the farm for its unpaid mortgage. Hector attempts to raise the money to pay off the debt but is informed by telegram he does not have the money (here the print is too damaged to actually read it) so Sam runs off and eventually finds the robber's money he stashed and pays off the debt. Suddenly here the film runs out so we don't know how it ended.

Like all the other surviving films of the later period of Ebony Pictures this film is in a distressed and fragmentary state suffering from significant water damage which makes parts of it impossible to make out (including two important letters the contents of which we must speculate) and the ending is also missing. The title make no apparent sense as the original Barnacle Bill was a character taken from a 19th century drinking song and was supposed to be a sailor, unless that is somehow explained by the missing footage although it's hard to see how. We can however see that this film is an improvement over the earlier film in that while the character played by Sam Robinson is an oaf he is within the bounds of white slapstick clowns as are the other more straight characters. The lawyer coming to enforce the foreclosure is also black and not a figure of mockery. The film does not rely on tropes left over from Minstrelsy and there is no use of the demeaning semi-literate dialogue. The George Lewis players appear to provide the cast for all subsequent Ebony Pictures and it's notable that the main two actors from the 1915 vaudeville film do not make an appearance again although it's possible the female character from that film is Evon Junior from this and subsequent films.

EVON JUNIOR

This film is a slight improvement over the previous film and less demeaning. The performances are slightly less broad but still fall within the slapstick genre. The plot is rambling and unfocused but at least it does have a plot. However while this film is better it was still subject to criticism in the Black press who wanted more serious and thoughtful portrayals of Black characters of the sort that Lincoln Pictures and Oscar Micheux were now making while Ebony Pictures were still focused on low-brow comedies. This would continue even while leaving behind the rural setting of this film for the big city that was more familiar to the Black audiences Ebony was aiming for.

"MERCY THE MUMMY MUMBLED" (1918);

Sam Robinson plays a hustler who comes up with a scheme to sell a fake mummy to a Professor (George Lewis) and buys a prop mummy case from a stage costumer and pays a sidekick (Tatum) to be wrapped up and pretend to be the mummy. He contacts an agent who examines the mummy and falls for the ruse buying it for $1000 after getting into a fight over the money. Meanwhile two agents for the Egyptian government are searching for lost mummies taken by American missionaries. Two delivery men are hired to transport the money by horse drawn wagon. While doing so the coffin with Tatum still inside falls off the wagon and is dragged through the streets. As the lid comes off Tatum scrambles to try to escape but the wagon drivers hit him on the head knocking him out, force him back into the coffin band continue to the professor's lab where he takes possession. Meanwhile the two Egyptian agents have tracked the delivery and show up at the lab to demand the return of the mummy but the professor throws them out. At this point the film halts with the ending being lost. Presumably they return and some sort of melee ensues with the "Mummy" coming back to life and emerging from his coffin, terrifying everybody into fleeing or causing a chase.

This film print is in better condition but it's also more truncated with more missing footage,inlcuding the ending which can only be guessed at. The story, what survives, is more coherent with more openings for slapstick hijinks. The plot is silly and outlandish but shows some imagination and could easily be the basis for a white Three Stooges short of later years. As in the previous film there is a scene involving an object containing a character being dragged behind a wagon at some speed which would have involved some skilled camerawork. Moving the story from a rural setting means the secondary characters are less country bumpkinish. The film's title had led some horror film historians to wonder if this film (long considered lost) might have been an early Mummy movie but we have enough to see that it clearly is not.

GEORGE LEWIS

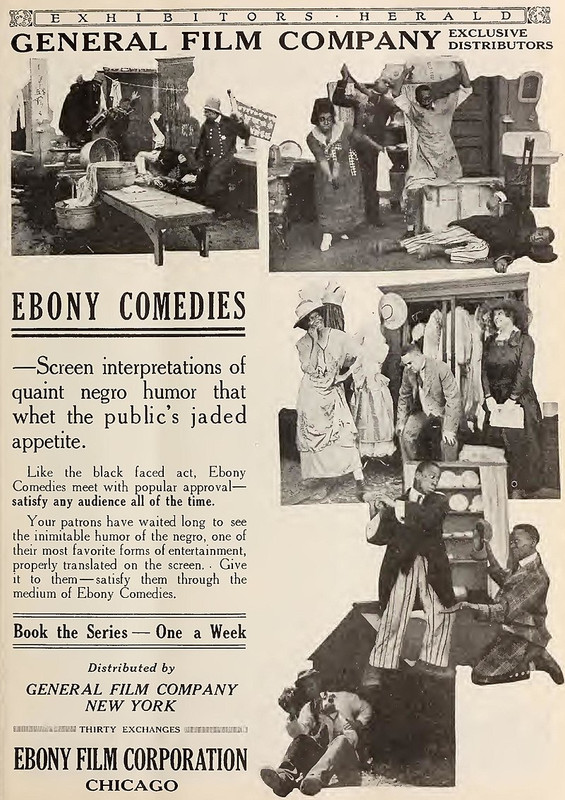

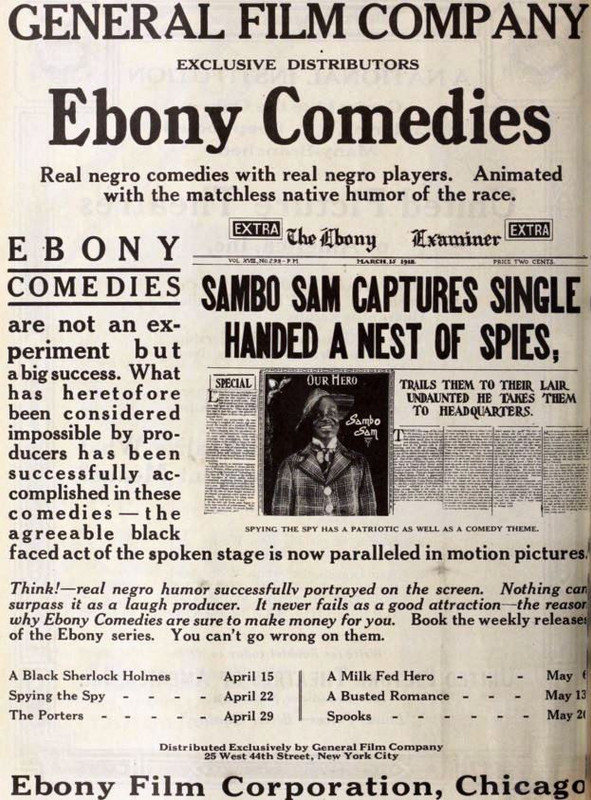

While the white owners of Ebony were willing to hire black artists and even put them into positions of production it's clear that whoever was in front or even behind the camera those in the office and marketing dept were clearly white and still aiming at a mostly white audience as one of their promotional packages sent out to theatre owners helpfully explains;

"Ebony Pictures are something different. Actors are Negros, just plain folks. If you know anything about THESE PEOPLE (emphasis mine) you must admit they are funny. Funniest people in the world. Bring a laugh when no others can. THEY (emphasis mine) are natural comedians, full of innate humor and pantomime which enables them to portray comedy as no one can. What colored Vaudeville acts mean as attractions to Vaudeville managers, Ebony Pictures will mean as attractions to the motion picture exhibits."

Obviously this was written by a white PR flack and aimed at white theatre owners appealing to white audiences as the use of terms like "these people" make clear. In spite of their, probably somewhat sincere attempts to broaden their appeal to black audiences they are also promising nothing more than cheap laughs with no suggestion of anything more. Another promo sheet enthuses;

"Ebony Comedies are not an experiment but a big success. What has heretofore been considered impossible by producers has been successfully accomplished in these comedies; The agreeable Black Faced act of the spoken stage is now paralleled in motion pictures."

Adding; "Think! Real Negro humor successfully portrayed on the screen." With another ad specifically chiming in "Unsurpassed as attractions for children".

Not all the promo sheets are this patronizing but the obvious target for them was clearly white theatre owners who are assured that these films are acceptable to white audiences with some (but not all) specifically using the term "Black Face" which was obviously aimed at white audiences. The only concession to Black sensibilities was the use of the term "Negro" which was then favoured by the Black Press and intellectuals instead of terms like "colored" (which also shows up) or the more insulting terms left over from Minstrelsy like "darkies". However in the same paragraph the unknown but almost certainly white writer switches back to using the term "colored". The Black press was not fooled with theatre and film editor Tony Langston of the black owned Chicago Defender urging theatre owners not to book the films saying they caused "respectable ladies and gentlemen to blush with shame and humiliation".

New Gerneral Manager Luther Pollard tried to push back on the image of Ebony Pictures being simply a ron t-for it's white owners writing in one to George P. Johnson of the black owned Lincoln Motion Picture Company, Pollard wrote that his comedies “proved to the public that colored players can put over good comedy without any of that crap shooting, chicken stealing, razor display, water melon eating stuff that the colored people generally have been a little disgusted in seeing. You do not find that stuff in Ebony comedies.” But his attempts, while by all accounts sincere, were constantly being undermined by the marketting tactics of his white employers.

One note that while production and casting of Ebony films after 1917 would be handled by Black artists there was at least one exception in Robert J Horner, a white screenwriter of less than savoury reputation who was listed as the writer of several of these films. One has to wonder if he was responsible for some of the Minstrelsy tropes that would remain.

After such an unpromising start at least some later Ebony films would show some improvements and while still sporting limited budgets would also include some somewhat more ambitious parodies of white films. It's worth remembering that the original black minstrel shows were also full of parodies of white fancy dress dances and fashions and had indeed started that way although white audiences were largely oblivious to this.

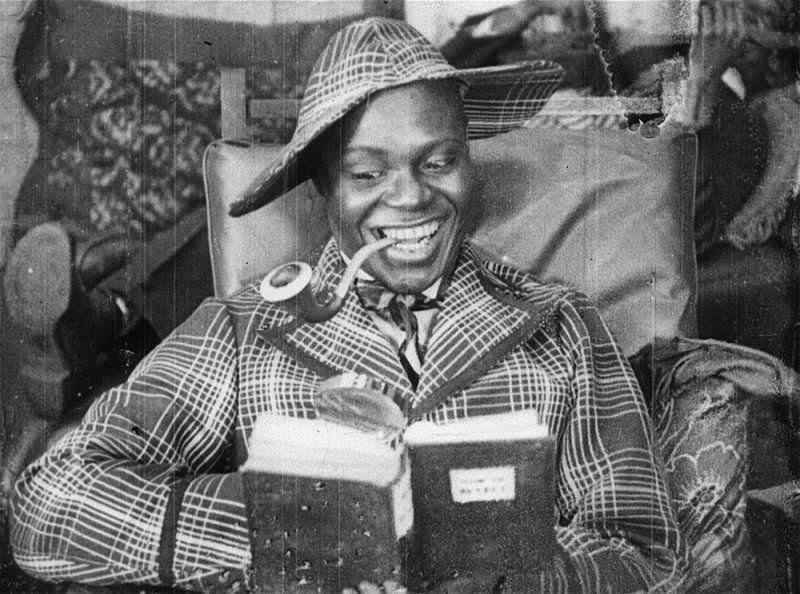

"A BLACK SHERLOCK HOLMES" (1918);

Sam Robinson is again the lead as a private detective Knick Garter (a play on the fictional detective Nick Carter already the subject of several books and films) who dresses like Sherlock Holmes wearing a deerstalker hat (sideways) and tweed suit sporting a large pipe and magnifying glass with his bumbling sidekick (Rudolph Tatum). The case involves a chemist (Lewis) who has invented a new type of explosive and is targeted by a conman (Sam Jacks) who eventually kidnaps the daughter (Evon Junior) who Garter/Holmes has a crush on. Garter/Holmes who is of the Inspector Clouseau school of inept detectives spies on the conman and gives chase ending in a shootout and rescue of the damsel in distress after which the conman meekly surrenders and one of his henchmen switches sides and runs off to elope with the daughter and they all live happily ever after which Garter/Holmes graciously accepts.

This one is actually complete albeit heavily distressed by water damage in some parts making those scenes a little difficult to fully follow however the story is essentially complete. The story is workable enough and Robinson has a more clearly defined character and look. Although long considered lost this is probably the best known Ebony film by the same sort of roundabout way that "Mercy The Mummy Mumbled" got a bit of notice by horror film historians, Sherlock Holmes historians had noticed this tile as an intriguing early Holmes film with a Black Sherlock but without having any details to work with. Now by actually viewing it we can see that it is obviously a parody of sorts. The story has nothing to actually do with Holmes of course and the characters are the usual broad comedy foils without too many carry-overs from Minstrelsy. Robinson is competent enough and the studio apparently saw enough potential in his bumbling detective to make a sequel of sorts.

"SPYING THE SPY" (1918);

Robinson's bumbling detective returns wearing the same deerstalker cap and tweed suit although this time his name has changed to Sam Sambo and he has no sidekick. With America now involved in World War One he has taken it upon himself to search for German spies and thinks he has found one named "Schwartz" who he makes a citizen's arrest of by throwing a bag over him and marching off to the police station. Once turned over to the police Schwartz is revealed to be a respectable black man (Schwartz is literally German for black) who the police promptly release, throwing Sam out of the station. Sam is however still convinced that Schwartz is a German spy and tails him as he goes into a building. It is revealed that Mr Schwartz is in fact a member of a Masons like secret society who are in the process of having an initiation ceremony dressed in dark hooded robes emblazoned with a skull & crossbones when Sam sneaks in. Recognizing Sam, Schwartz decides to turn the tables and put him through the ritual which includes dumping him into a jail cell with an animated skeleton and a simulated beheading. After terrorizing Sam the group allows him to escape by slipping him a gun with blanks and when he shoots it they all fall "dead" and he runs off. Finis.

Unlike "A Black Sherlock Holmes" this film has not been noticed by Holmes historians but Robinson clearly plays the same character (albeit with a different name) although if anything he's even dumber this time. This is still a lowest denominator slapstick; some film historians have suggested that there might be a theme of mocking "A Birth Of A Nation" in the secret society with their robes and hoods terrorizing Sam. However this is reading too much into this film (probably based more on the promotional posters rather than viewing the actual film which was long thought lost) the robed figures are clearly black and are not real villains committing any actual violence and Sam is not a real victim but is a oafish clod who besides being in the wrong has even assaulted and kidnapped Mr Schwartz early in the film. Schwartz and the robed characters are presented as respectable middle-class men and definitely not Klansmen. In fact there actually were all-black counterparts of the all-white Masons including the Prince Hall Masons who still exist. Additionally unlike most of the later Ebony films of the Pollard era there are white characters in the role of the police officers who are minor characters but they behave fairly and responsibly. There is no explicitly or implicitly racial critique to be found here. In fact, changing the name of the Robinson character from Nick Garter, a mild parody of a white fictional character, to Sambo, an explicitly racist Minstrelsy trope is even a step backwards.

We can't be sure exactly in what order the later Ebony films were actually made. At least two dozen films were released in 1917 and 1918 with "A Black Sherlock Holmes" listed as released in April 15 1918 and "Spying The Spy" in April 22 however they were probably not filmed in that sequence as there are clearly large snow drifts to be seen in "Spying The Spy" so it must have been filmed in the winter of 1917-1918 but no earlier as America did not declare war in Germany until April 1917. Thus "Sherlock Holmes" might have been filmed afterwards with the name change from Sambo to Nick Garter being an update for a character who was considered as a possible recurring role.

SAM ROBINSON

That would never happen as Ebony Films attempts to rebrand for Black audiences would never be really accepted and would continue to face criticism from the Black press like the Chicago Defender who called for a boycott. To make things worse the studio continued to re-release their earlier films. As the studio was trying to market to both Black and white audiences some of the promotional posters and title cards also continued to use blackface imagery which may have amused whites but did not go unnoticed by the Defender. Ebony's attempts to play both sides were bound to fail and by 1919 Ebony closed up shop for good. There may have been other factors; at the end of the Great War there was an economic recession and more importantly the larger film industry which had originally been based in New York and New Jersey was packing up and moving to Hollywood. Ebony would not be among them, in fact out of Ebony's Black cast and producers virtually none would have any known film credits after Ebony shut down. It could be that none of them made the move to Hollywood and instead stayed in Chicago or made their way to New York and worked on the Vaudeville stage. While the films of Ebony Pictures have some historical interest as artifacts of early Black cinema it can't really be said that Ebony itself left any real legacy as all it's films were soon lost and forgotten and unlike some other failed studios, record labels and publishing houses none of it's creative staff would use their experience to make other films. The one odd exception was white screenwriter Robert J Horner who did make his way to Hollywood where he would have a long if undistinguished career as a director and producer in spite of having only one eye, no working legs and no apparent talent. He would carry on the fringes of Poverty Row making notoriously low quality B Movie (or lower) Westerns considered some of the worst of a not very demanding genre and dodging lawsuits, creditors and fraud arrests until his death in 1949.

ROBERT J HORNER

Sam Robinson has been named by some sources as a younger brother of Bill Bojangles Robinson, later known as the famed tap dancer and already fairly well known as a Vaudeville player. But was he really? The backstory is complicated. Bojangles (whose actual birth name was Luther) is known to have had a younger brother named Bill. As he entered show business Luther decided that Luther wasn't a good stage name and switched to his brother's name of Bill. In spite of his cheery and unflappable public image in private Bojangles was known to be rather stubborn and quick tempered and he convinced (or bullied) his younger brother to go along with this and so when he then in turn eventually entered show business as a musician he changed his name to Percy. It's possible that before adopting the name of Percy as a musician he started out as an actor under the name Sam. Sam Robinson's film credits (which include an early Mary Pickford film) have has no other (known) film credits after Ebony Films shut down so if Sam and Percy are indeed he same person he could have quit acting and switched to music under the name Percy in order to dodge the bad press these film had gotten in the Black press. No other Robinson brother is listed however there is also a problem with the birthdate given for Sam as he is listed as being born in 1888 in Richmond, Virginia, which was the home of Bill who was born in 1878. However the brother's parents are known to have died in 1884 whereupon the brothers were raised by their grandparents with no known step brothers. It's possible that Sam is also Percy and the 1888 birth date given is simply wrong. It's also possible Sam might have been a cousin rather than brother who billed himself as such however it's more likely that the later claim that Sam was one of the Robinson Brothers was a mistake made by a later writer based on the coincidence of having the same name (admittedly not uncommon) and coming from the same town at roughly the same time.

All this leaves open the possibilities that Sam Robinson;

a) May in fact have been Percy, the younger brother of Bojangles acting under yet another different name (his real name being Bill remember) and the listed birthdate of 1888 is simply wrong as both parents died in 1884. Since Percy was known as a working musician he may have used the alias Sam since the Ebony Films were not popular in the black community and might have detracted from his musical career.

b) He may have had some other family connection with Bojangles and Percy, perhaps a younger cousin, exploiting the same last name by claiming he was yet another brother.

c) He may have had no connection at all and had adopted the persona either coincidentally having the real name Sam Robinson (hardly an unsusal name) or with that being an entirely made up stage name.

d) It's also possible that Sam Robinson was indeed his real name and that some latter day researcher just assumed that he was a younger brother to Bojangles and listed him as such and since everybody involved is long dead there is nobody to ask.

A close look at the census reports for Richmond, Virginia in the 1880's might clear this up but we may never know for sure. At any rate Sam Robinson is listed as dying in 1971 (assuming that's true) but with no other film credits. As Ebony Films was closing up shop in Chicago the film industry was also moving to Hollywood and if Sam didn't want to relocate and stayed in Chicago then that would explain why he has no other film credits. He could have stayed on in Chicago with the George Lewis players and worked in vaudeville, continued on as a musician (as Percy) or perhaps he simply retired from show biz. At any rate the question as to who exactly Sam Robinson was or wasn't is a bigger mystery than the ones faced by Knick Garter.

SAM ROBINSON

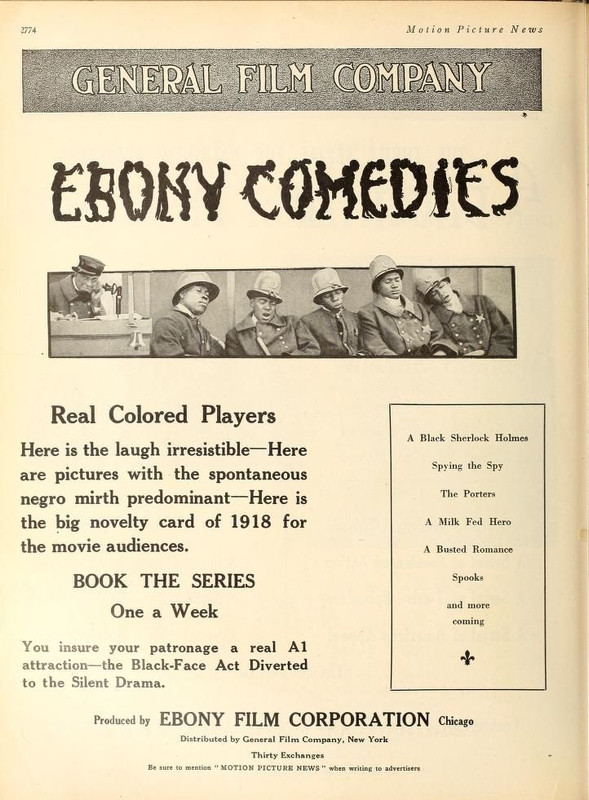

The failure of Ebony Films to attract a Black audience can be traced to a few reasons. While the later films are typical enough of white slapstick films of the era and are usually competently done and performed and if they had been made a few years earlier or perhaps even a few years later they might have been acceptable enough if not exactly respectable guilty pleasures. By modern standards they are not notably different from the films then being made by Mack Sennett starring the likes of Fatty Arbuckle, Ben Turpin and the Keystone Kops with one promotional flyer actually shows a group of dozing Black policeman implying they may have made a Keystone Kops type short now lost, with the Sergent showing a distinct and probably not coincidental resemblance to the white actor Ford Sterling who played the same role in the actual Keystone Kops series. If anything in fact they are actually more restrainedthan the Sennet films. Sam Robinson is photogenic enough and shows some skill with physical comedy and it's easy to see how Ebony producers saw him as a possible comedy leading man.

PROMO SHEET SHOWING BLACK KEYSTONE KOPS

Indeed at the same time these films were being made the Black comic Bert Williams was a legitimate star playing bumbling sad sacks, and in the early sound era Spencer Williams would have career as both an actor and writer/director making a series of all-black films that were popular with Black audiences in the 1930's and 40's including broad comedies. In fact Bert Williams was the first Black multi-media star as a success on film and stage with hit records and sheet music and if he hadn't died in 1922 he almost certainly would have continued into the twenties and would be better remembered today. Williams was certainly more talented than Robinson with his characters having depth and vulnerability and he was seen as a figure who had worked his way for years through the white world while maintaining his dignity and was a genuinely popular figure with both blacks and whites as well and among the major stars of the day. For comparison note the subtley and pathos in his most famous routine from "A Natural Born Gambler" (1916) in which Williams, playing a luckless card-shark, ends up in jail playing a hand of invisible poker with himself and still losing.

BERT WILLIAMS IN "A NATURAL BORN GAMBLER" (1916);

Ebony were never able to shake their image of being a white owned studio cynically attempting to appeal to black audiences by hiring some black performers and those audiences saw through this whether or not that's entirely fair, especially to those performers themselves. This perception was certainly not helped by the continued use of Minstrel show images in the title cards in some of the films, the use of Minstrel show names like Sambo and Rastus and the patronizing tone of the promotional material which even if the general public did not see was seen by the press. Ultimately in the wake of "Birth Of A Nation" the Black community, it's leaders and especially the Black press was simply no longer prepared to put up with the slights, insults and patronizing attitudes they saw in the entire Ebony Pictures project. They wanted films and literature that treated them seriously and thoughtfully and they were already getting that from filmmakers like Oscar Micheux and Lincoln Pictures. In fact from the end of Ebony Films in 1919 and the death of Bert Williams there were no known Black comedy films made for a decade until the sound era. A decade later when Spencer Williams was making his films, at least some which included some broad slapstick humour (he would infamously later appear in "Amos & Andy" films) black audiences were more prepared to accept some silliness but 1917 to 1919 were no time for frivolity. Even if Ebony had been more thoughtful and sensitive in their presentation there was simply no demand for what they were offering in Black America at that time.

No comments:

Post a Comment